By Vickie Wallace and Alyssa Siegel-Miles

In 2010, Connecticut law banned the use of EPA registered pesticides on school grounds (Connecticut General Assembly, 2009). This legislation has compelled school grounds managers (SGM) to think proactively and make fundamental changes to their management programs. SGM must now emphasize sound cultural practices. Pest management (in particular, weed management) has presented a serious maintenance challenge on school ground properties.

Pesticide-free management requires significant alterations to pest control strategy. In the past, many school grounds managers incorporated chemical products into their maintenance regime to manage weeds, insects, and/or diseases, either preventatively or curatively. SGM must now navigate a complex web of information to identify effective methods to manage or control pests. Additionally, pesticide-free school grounds maintenance requires an increase in time, commitment, and labor resources (Bartholomew, Campbell, Wallace, 2015). Lacking a corresponding increase in school maintenance budgets, many SGM struggle with pesticide-free management programs.

The purpose of this document is to provide guidance for effective maintenance of pesticide-free school landscapes. Research-based information has been utilized throughout this document to provide sound horticultural recommendations.

Implementing realistic, sound cultural practices throughout the year will help improve aesthetics, promote sustainability, and enhance the health of plants on school grounds. Attractive, uncluttered landscaping (Figure 1) on school properties reduces stress and improves the quality of life for school faculty, staff, and students (Dyment & Bell, 2007, Matsouka, 2010).

This publication will address the primary cultural practices for managing pesticide-free school landscaped areas: pre-plant practices, fertilization, irrigation, pest management, plant selection, and other maintenance tasks, such as pruning. Sustainable plant selection for both central and periphery areas will be covered.

For guidance and information on school pesticide-free athletic fields, refer to Best Management Practices for Pesticide-Free, Cool-Season Athletic Fields, Second Edition (s.uconn.edu/UConnAthletic FieldBMP).

EXAMPLES OF TOPICS DISCUSSED:

- Connecticut's Pesticide Law

- Sustainable Landscaping Principles

- Plant Selection

- Preparation and design

- Sustainable High Visibility Areas

- Courtyards, Lawns

- Sustainable Naturalized Areas

- Meadows/Tall Grass Areas

- Wetlands

- Plant Health Care, Cultural Practices, and Maintenance of School Grounds

- Pest Control

And more! Read the complete document here.

CONNECTICUT’S PESTICIDE LAW

Connecticut state legislation banned the application of all pesticides registered with the U.S. EPA, and labeled for use on lawn, garden, and ornamental sites, on the grounds of public or private day cares (as defined in CGS Sec. 19a-77) and schools with grades K-8. The text of the law (C.G.S. Sec. 10-231) can be read at ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu/school-ipm or at portal.ct.gov/deep/pesticides.

The law applies to:

- Landscaped areas around buildings and anywhere on K-8 school grounds, including trees;

- Turfgrass areas: lawns, athletic fields, and recreational areas (Figure 2);

- High school property that is shared jointly and used by day care or K-8 school students;

- Playgrounds (school or municipal);

- Fence lines around athletic fields, tennis courts, playgrounds, or school property perimeters;

- Parking lots and sidewalks on school grounds;

- Peripheries/boundaries of the school property

The term “pesticide” (i.e., products that kill, repel, or control animal or plant pests) includes herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and rodenticides. Antimicrobial agents, pesticide bait, sanitizers, disinfectants, and aerosol sprays that protect from imminent danger from stinging or biting insects are not prohibited under the law.

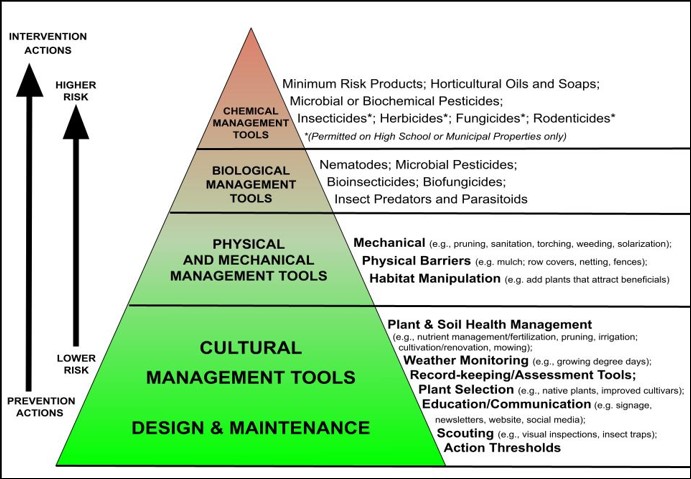

EPA exempt, “minimum risk” 25(b) pesticides are the only products allowed at day care and K-8 school properties in CT (Figure 3). Exceptions include the use of some EPA registered pesticide products, including horticultural oils and soaps, and microbial or biochemical pesticides on K-8 school grounds. For these products to be available for use in CT, they must be registered (and renewed annually) with CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP). CT DEEP maintains a list of “minimum risk” pesticide products allowed for use at K-8 schools and day care centers, which can be found at portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Pesticides/Information-Look-up. Learn more at Biological Pest Control for Connecticut School Grounds (ipm.cahnr.uconn. edu/school-ipm). Per CGS Section 22a-63, violators of CT’s pesticide law can be fined up to $5000 and/or imprisoned up to one year.

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

- Use all products according to label recommendations.

- Pesticide products with an EPA registration number, whether synthetic or organic, cannot be used on day care/K-8 school properties (apart from the exceptions mentioned above).

- EPA registered pesticides may be considered a component of the maintenance care program for municipal areas or high schools that are distinct and separated from day care and K-8 school properties and municipal playgrounds.

- While minimum risk products may pose little to no risk to human health or the environment, their exemption from EPA registration means they also are not subject to rigorous, science-based evaluation and testing. Product efficacy cannot be substantiated. These products are most effective when used in combination with a comprehensive program of best management practices.

- Minimum risk 25(b) products, like all pesticides, require a licensed pesticide applicator to apply on any/all school properties and municipal playgrounds in the state of CT. There are two levels of pesticide license - supervisor and junior operator. A junior operator works under the direction of a supervisor licensee, who is responsible for deciding whether and how pesticides will be used. Applications can also be contracted to a landscaping/lawn care company that is registered with DEEP as a commercial pesticide application business and whose employees hold commercial pesticide certification.

- If an IPM policy is in place for the school district, all pesticide products used on school grounds must be referenced in the district’s IPM plan. It is important to include all products that MIGHT be considered or are used, even those that may only be used when an emergency application is necessary. Private schools are not required to have a policy statement or write an IPM plan.

- The law requires that any pesticides used on school grounds are listed annually on the school website.

- Any pesticide used on school grounds, municipal playgrounds, or day care properties must be registered with the state of CT. The law requires that all pesticides are used according to label instructions. Homemade recipes (including those crafted with or containing minimum risk ingredients) are not permitted on school properties.

For more information on Connecticut’s Pesticide Law, see A School Grounds Manager’s Primer: Connecticut’s Pesticide Ban on School Grounds (ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu/ct_pesticide_ban_schools).

Read the complete School Landscapes BMP document here: ipm-cahnr.media.uconn.edu/UConn-School-Landscapes-Best-Management-Practices.pdf

SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPING PRINCIPLES

K-8 school grounds and athletic field managers have utilized Integrated Pest Management (IPM) protocol for many years. Use of sound IPM principles has become even more critical due to the restrictions and limitations of products available for use in a pesticide-free environment. Connecticut is one of only two U.S. states with a state-wide pesticide ban for the grounds of K-8 schools and day care centers.

IPM is a system of pest management practices that uses all available pest control techniques. The goal of an IPM program is to manage a pest population at or below an acceptable threshold level, while decreasing the overall use of pesticides.

Often, preventive, cultural, and mechanical tactics are successful, which can substantially reduce the need for chemical applications. IPM practitioners always strive to address and correct the root causes of pest problems.

Healthy, sustainable school landscapes provide environmental advantages and support educational opportunities for the school community. By necessity, municipal and facility managers that maintain school properties must prioritize compliance with the law and school safety, while managing limited budgets. At the same time, managers can also improve the sustainability and environmental benefits of school landscapes.

School properties are an environmental asset. Well landscaped school properties (even with modest or limited budgets) are a valuable resource that enhance learning and improve the quality of life for school constituents. School landscapes can be stimulating, visually pleasing, and conducive to learning. School properties can improve biodiversity by increasing the usage of native plants and decreasing the nonrenewable inputs used to maintain the landscape. They can even serve as a pathway for pollinators and other insects or as a habitat corridor for birds and wildlife (refer to pollinator-pathway.org/connecticut for more information).

Benefits of increasing landscape sustainability on school grounds include:

- Expansion or creation of an outdoor classroom and learning environment that provides year round interest and visual pleasure for students and faculty (Figure 5).

- Support of pollinator habitats and enhanced biodiversity.

- Increase of permeable/plant cover, which boosts carbon sequestration, the capture and storage of carbon dioxide in the plants and soil. Dense, healthy turfgrass and plants in the landscape sequester carbon, which helps moderate air temperatures surrounding the school building and provides an efficient carbon sink, preventing carbon dioxide from entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Carbon sequestration benefits the whole community and is enhanced by properly landscaped school properties.

- Protection of soils, natural vegetative cover, water resources, and water quality.

- Opportunity for reduced maintenance of high visibility and non-priority turfgrass areas, utilizing fewer inputs (i.e., fertilizer, water, chemicals, and fuel).

Essential elements of an IPM program include:

- Accurate pest and beneficial insect identification. Incorrect identification of pests is a common source of pest control failure and unnecessary plant damage.

- Understanding life cycles, including the pest development stage that causes damage.

- Understanding the role of beneficials.

- Identifying the root cause of any pest problem, including abiotic factors that can contribute to plant decline (e.g., ensuring that water, sunlight, site and soil conditions are properly matched with plant needs).

- Ongoing scouting and monitoring to determine pest severity and presence of beneficials. Identify the action threshold - the level of pest population when control of the pest(s) will be required to prevent or minimize unacceptable levels of damage to turf or ornamental plants.

- Understanding the survival needs of existing or potential pests, including food, water, and shelter. Pest populations can be successfully managed through proper sanitation and control of environmental conditions (e.g., removing food and water sources that feed pests).

- Thorough record-keeping, including weather data, pest and beneficial populations, plant conditions, and management tactics.

- Evaluating the success of management tactics.

Learn more at EPA.gov/managing-pests-schools and ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu/school-ipm.

Read the complete School Landscapes BMP document here: ipm-cahnr.media.uconn.edu/UConn-School-Landscapes-Best-Management-Practices.pdf

PLANT SELECTION

PRINCIPLES

- Proper plant selection is the most important step in designing a sustainable landscape.

- “Right plant, right place” is the fundamental principle for the environmentally sound management of landscapes. Plants should be selected for not only aesthetic value, but also because they are adapted to the existing microclimate, including soil and water conditions.

- Plants selected should be biologically diverse and allow for reduced irrigation, fertilizer, and soil amendment inputs, as well as reduced costs associated with labor.

- Establishing strong, healthy, dense plantings is crucial for pest management in sustainable school landscapes. A vigorous, healthy, unstressed plant can usually survive, avoid, or outcompete many potential disease, insect, and weed pests without further intervention by grounds managers.

- Native plants are best adapted to the local soils and site conditions. Incorporating native plants helps to restore local ecosystems that support a wide variety of indigenous and beneficial insect, bird, and animal species. Whenever new construction or building renovation occurs, the design of the landscaped areas, including in the high visibility focal points (Figure 6), should be amended to include site-appropriate native plant material. Over time, as these native plants become established, they can increase biodiversity and contribute to a reduction in expense and time spent on maintenance.

A healthy and diverse landscape supports naturally occurring beneficial insects. Native predators and parasitoids will help control harmful pests when provided the opportunity and necessary habitat for their survival. Many practices that support pollinators also support beneficial predators.

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

PREPARATION

- Complete a detailed site assessment, such as the UConn Landscape Assessment Form (ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu/school-ipm).

- Perform a soil test (soiltest.uconn.edu) when renovating landscapes or when analyzing problems. If warranted, use organic amendments (e.g., compost, compost tea, or leaf mulch), calibrated as part of the overall nutrient management plan, to build soil organic matter and improve soil health, establish populations of beneficial soil organisms, and extend nutrient release.

- Assess the soil health and growing conditions of each landscape site. Factors that influence the rate of plant dehydration include soil type, topography, and exposure to wind and sunlight. Different areas of a school property may vary greatly in these characteristics, which will have a significant impact on the plants chosen for each area.

- Select appropriate plants for the site(s) based on sunlight requirements, wind, soil conditions, and water availability to ensure successful establishment. Utilize UConn’s Native Plant & Sustainable Landscaping Guide as a resource (s.uconn.edu/UConnNativePlantGuide).

DESIGN

- Landscape design on school properties should:

- Provide a safe, calming environment that fosters learning, offers an aesthetically appealing design, and does not pose a security concern by physically or visually impeding visibility from within or outside the school.

- Remain economically sustainable, considering both the installation and the long-term seasonal maintenance.

- Protect environmental resources, including water.

- Include plants that remain healthy and attractive all season-long with reduced maintenance.

- Produce limited plant litter for reduced annual maintenance (refer to Table 3, Appendix).

- Deter wildlife activity near buildings.

- Minimize bee attraction near key entryways or areas frequently visited by students.

- Ensure that plants are not placed too close to the building foundation, to reduce the ability of ants and termites to travel into the school building.

- Avoid obstructing windows or visibility near entrances.

- Select plants based on the soil characteristics, climate, sun exposure, water availability, and pest concerns. Match plants with correct growing conditions, to reduce unnecessary irrigation and fertilizer inputs. Pair plants with their preferred native soil type (i.e., clay, sand, silt) and sun exposure (i.e., sunny vs. shady) (Figure 7).

- Group plants together with similar water, pH, and nutrient requirements to allow for the most efficient use of resources.

- Plant in "floral clumps,” which imitates the way plants naturally seed themselves and is both aesthetically pleasing and beneficial for pollinators (Figure 8). It is easier for pollinators to locate and benefit from plantings when there are five or more of each pollinator-supporting species in a group (Credit Valley Conservation, 2017).

- Utilize a diverse range of plant species. Choose plants that offer ornamental interest in every season, especially from fall through late spring, when staff, students, and visitors who regularly frequent the building can appreciate them. Bark, foliage, fruit, and fragrance are ornamental characteristics to consider in addition to flowers.

- Select flowers with a variety of colors, shapes, sizes, heights, and growth habits to attract pollinators. Choose plants with a wide range of flowering times to extend the forage season and attractiveness of the planting. Native plants that bloom and attract pollinators in spring (e.g., willow, golden alexander) or fall (e.g., ironweed (Figure 10), goldenrod, aster) will provide more opportunities for student observation and learning from pollinator activity.

- Consider including species that support both butterfly/moth larvae and adults. Many butterfly and moth species are highly specialized, requiring specific foods for their survival (e.g., monarch caterpillars can only survive by consuming milkweed plants). To reap the benefit of supporting pollinators and providing the educational environment for students, it is important to consider some plants that will be tolerated being eaten by these beneficial species. Many trees, too, are butterfly larval host plants, including oak, maple, and willow (refer to Table 1, Appendix).

- Use plants that, once established, will perform well over time. Select plants that do not require excess care to maintain (e.g., frequent pruning).

- Ensure that the mature height and spread of each plant is accounted for to avoid the need for excessive pruning or regular replacement.

- Select trees and shrubs that produce minimal litter (e.g., fruit, nuts, berries, seed pods) where children actively frequent, which may pose a potential health hazard and to minimize additional maintenance (refer to Table 4, Appendix).

- For high visibility areas, “nativars” may be of value. Nativars are cultivars and hybrids derived from native plants. Some nativars provide as much benefit for pollinators as straight species, while others do not. They are often more compact or designed to suit smaller spaces, making them potentially more appropriate for courtyards or entryways where there may be an expectation for a tidy garden.

- Avoid cultivars that have been bred as double flowers: they are typically sterile or it may be difficult for pollinators to access double flowers’ nectar and pollen. A sterile plant will not be able to provide seeds for birds that rely on them as a food source.

- Each nativar plant is a clone, reducing genetic diversity in the plant stand. In lower visibility or ancillary areas, consider planting primarily straight species of native plants, where they can provide increased support for pollinators and other wildlife.

- While numerous studies suggest that many pollinators prefer to forage from native plants (White, 2017), some non-native plants are also attractive and supportive to pollinators. As long as they are not invasive, these plants are good contenders for a sustainable garden, including: Allium, Catmint, Salvia, Hydrangea, Lavender, Sedum, Russian sage, Sweet clover, Zinnia

- Choose salt tolerant plants in areas near sidewalks and parking lots that receive winter ice melt treatments.

- Select plant material not regularly browsed by deer. Refer to Table 5 in the Appendix and the fact sheet Strategies to Minimize Deer Damage on School Grounds (ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu) for more information.

UConn’s Native Plant & Sustainable Landscaping Guide (ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu) and Connecticut’s Pollinator Pathways are useful resources for information on plant selection.

Monarch Butterfly Conservation Garden Tips and Tricks

- Make sure milkweeds are easily accessible and visible to butterflies (e.g., do not plant grasses or other concealers in front of them). Plant milkweeds in an area with open lines of-sight (especially north and south) and on the perimeter of the garden to increase visibility.

- Use a variety of milkweed species. Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is very attractive to egg-laying butterflies (Figure 9), while butterfly milkweed (A. tuberosa) supports both butterflies and a wide variety of native bees.

- Swamp milkweed and butterfly milkweed cultivars have been found to be as suitable for supporting monarch eggs and larvae development as the straight species (Baker et al., 2020).

- Plant late season flowering plants to support monarch migration (e.g., Mexican sunflower, zinnia, goldenrod).

Adapted from “Monarch Butterfly Conservation Garden Tips and Tricks” by Adam Baker.

Read the complete School Landscapes BMP document here: ipm-cahnr.media.uconn.edu/UConn-School-Landscapes-Best-Management-Practices.pdf

SELECT REFERENCES:

- Bartholomew, C., B. Campbell, V. Wallace. 2015. Factors Affecting School Grounds and Athletic Field Quality after Pesticide Bans: The Case of Connecticut. HortScience. 50(1):99-103.

- Connecticut General Assembly. 2009. An Act Concerning Pesticide Applications at Child Day Care Centers and Schools. cga.ct.gov/asp/cgabillstatus/cgabillstatus.asp?selBillType=Public+Act&which_year=2009&bill_num=56

- Dyment, J. and A. C. Bell. 2007. Active by Design: Promoting Physical Activity through School Ground Greening. Children's Geographies. 5:4, 463-477, DOI: 10.1080/14733280701631965

- Matsuoka, R.H. 2010. Student Performance and High School Landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97, pp. 273-282

Read the complete School Landscapes BMP document here: ipm-cahnr.media.uconn.edu/UConn-School-Landscapes-Best-Management-Practices.pdf

Questions? Contact:

Vickie Wallace

UConn Extension

Extension Educator

Sustainable Turf and Landscape

Phone: (860) 885-2826

Email: victoria.wallace@uconn.edu

Web: ipm.uconn.edu/school

Photos by Alyssa Siegel-Miles and Victoria Wallace.

UConn is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.

©UConn Extension. All rights reserved.