By Victoria Wallace and Alyssa Siegel-Miles, UConn Extension

Regular scouting of lawn and landscape areas for pests, including weeds, is a critical component of a sound Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach. When plants in the landscape are stressed due to environmental conditions that provide less than optimal growing conditions, weeds can easily establish and compete for nutrients, sunlight, water, and space. The key to managing weeds in the landscape is preventing conditions that allow for weed invasion and implementing proper cultural practices.

The simplest definition of a weed is “a plant growing where it is not wanted.” Weeds can be found in any location; however, many favor and populate an area in greater concentration in specific soil conditions. Prevalent in many landscapes, these weeds are referred to as “indicator weeds,” as they provide clues relating to the health of the soil, nutrients present, growing conditions, and the potential health of the landscape plants. Recognizing the conditions in which they usually grow, and looking within those site parameters to select plant material appropriate to those particular site conditions, is part of a long-term successful strategy that can displace weeds with more favorable plants. Soil conditions that directly affect plant growth include acidity, excess moisture, drought, compaction, low light, and low fertility.

To reduce weed infestations, one of two strategies can generally be employed:

1. Ensure that plants in each landscape location are suitable for the existing conditions.

- Desired plants growing in unsuitable growing conditions will lead to poor health and open areas. Weeds will germinate and fill in any bare soil.

- The more ground that is covered by appropriate, desirable plants, or mulch, the fewer spaces weeds will have to infiltrate and establish. Encourage the health of the desired landscape plants to discourage weed populations.

- Challenging areas, such as those that stay wet for the majority of the year, can become a valuable asset when embraced and incorporated into the overall garden design.

2. The soil can be amended to accommodate desired plants that prefer differing conditions, which will also discourage the current weeds from growing.

- For example, if weeds present in an area indicate that the soil to be planted is infertile or of poor quality, and plants that require higher fertility are desired (e.g., tomatoes, annual flowering plants, roses), the soil can be amended with compost (once the quantity needed is confirmed with a soil test). As the soil fertility is improved over time, it will support the desired plants’ needs and discourage the survival of those weeds that prefer or require a more infertile soil.

The success of any weed management strategy should depend first on the identification and biology of the weed, then coordinating the proper identification with the correct timing and method of establishment. Understanding the life cycle of the weeds present in the landscape helps to determine the most effective control strategy to discourage their growth.

Low Fertility Soils

To reduce weeds in an area of low fertility, test the soil to obtain an accurate indication of which nutrients are deficient. If desired plants are those that require a high or more neutral fertility program, amend the soil as needed with compost, cover crops, or organic fertilizers, such as fish meal or bonemeal, to raise the pH and add nutrients.

Alternately, plant the area with desirable species that are recognized to thrive with few nutrients.

These include:

Ornamental Perennials:

blanket flower (Gaillardia x grandiflora)

coreopsis (Coreopsis spp.)

globe thistle (Echinops ritro)

goldenrod, sweet (Solidago odora)

goldenrod, gray (Solidago nemoralis)

lamb’s ears (Stachys byzantina)

ornamental sage (Salvia spp.)

rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

silvermound (Artemisia schmidtiana)

yarrow (Achillea spp.)

Ornamental Shrubs:

American filbert (Corylus americana)

bayberry (Morella pensylvanica)

beaked filbert (Corylus cornuta)

Northern bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica ‘Gro-Low’)

ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

shrubby potentilla (Potentilla fruticosa)

Solution plants:

USE THESE WEEDS TO IDENTIFY LOW FERTILITY SOILS:

| Common Name (Botanical Name) | Life Cycle |

| Common mullein (Verbascum thapsus) | Biennial |

| Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) (invasive) | Perennial |

| Plantain (Plantago spp.)* | Perennial |

| Red (sheep) sorrel (Rumex acetosella)* | Perennial |

| White clover (Trifolium repens)* | Perennial |

*Found in multiple categories.

Low fertility loving weeds: broadleaf plantain (above); mugwort (below)

‘Gro-Low’ fragrant sumac is a problem-solving shrub – perfect for school landscaping beds, parking lot islands, and steep banks. Photo by Alyssa Siegel-Miles.

Northern bush honeysuckle is a versatile native shrub that thrives in sun or part shade and is very drought tolerant. Photo by Alyssa Siegel-Miles.

Acidic Soils

Acidic (sour) soils have a pH below 6 (a pH of 7 is neutral, above 7 is alkaline). Most garden plants grow best when the soil pH is between 6.0 and 7.2. At a neutral pH, some of the most important nutrients are most readily available to plants. If the soil pH is too high or low, phosphorus (responsible for helping a plant produce blooms and fruit), and several other nutrients become insoluble and unavailable to plants. Some other nutrients, such as iron, copper, and zinc, are more readily available when the soil is more acidic. Plants that thrive in acidic soils require more of these nutrients. Plants that thrive with high quantities of nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium, which are more available at a neutral pH, include many introduced, non-native ornamentals and most vegetable plants.

To reduce weed populations in acidic soils, select and plant species, including many natives, that naturally prefer and thrive in an acidic soil. Plantings thick with acid-loving plants will keep weeds to a minimum. Acid-loving plants include:

azalea hydrangea

bleeding heart Japanese pieris

blueberry magnolia

dogwood pine

elderberry rhododendron

ferns (all types) rhubarb

fothergilla viburnum

Alternately, if plants that are challenged to tolerate and persist in acidic soils are desired, such as many vegetable plants and some ornamentals (e.g., lilacs, clematis), amend the soil to raise the pH by incorporating the appropriate amount of dolomitic limestone and compost into the soil (based on soil test results).

Acid-loving weeds:

USE THESE WEEDS TO IDENTIFY ACIDIC SOILS:

| Common Name (Botanical Name) | Life Cycle |

| Bentgrass (Agrostis spp.) | Perennial |

| Broadleaf plantain (Plantago major)* | Perennial |

| Silver cinquefoil (Potentilla argentea)* | Perennial |

| Hawkweed (Hieracium spp.) | Perennial |

| Knapweed (Centaurea spp.) | Summer Annual |

| Lady's-thumb smartweed (Polygonum persicaria)* | Summer Annual |

| Prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare)* | Summer Annual |

| Red (sheep) sorrel (Rumex acetosella)* | Perennial |

| Sowthistle (Sonchus spp.) | Perennial |

Hawkweed foliage.

Red sorrel flowers.

Red sorrel foliage

Wet Soils

Wet areas in the landscape are a valuable asset when they are embraced and incorporated into the overall garden design. Efforts to change the soil conditions are likely to be costly and labor intensive, but often are not successful. Design wet areas to serve as “natural” rain gardens. Planted with desirable species that thrive with “wet feet,” rain gardens allow rainwater runoff to infiltrate and be absorbed into the soil. They clean, slow the rate of infiltration, and reduce the volume of stormwater. Specific, appropriate plants, which can withstand the extremes of moisture and concentrations of nutrients (particularly nitrogen and phosphorus) often found in stormwater runoff, are utilized.

Plants that thrive in a rain garden include:

blue flag iris (Iris versicolor)

cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

curly willow (Salix matsudana)

dogwood (Swida spp., previously Cornus spp.)

joepye weed (Eutrochium purpureum)

pussy willow (Salix discolor)

river birch (Betula nigra)

soft rush (Juncus effusus)

swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

white turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

For more information, download the Rain Garden app developed by UConn’s NEMO Program.

USE THESE WEEDS TO IDENTIFY WET SOILS:

| Common Name (Botanical Name) | Life Cycle |

| Annual bluegrass (Poa annua)* | Winter Annual |

| Common chickweed (Stellaria media)* | Winter Annual |

| Curly dock (Rumex crispus) | Perennial |

| Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) | Perennial |

| Lady’s-thumb smartweed (Polygonum persicaria)* | Summer Annual |

| Mouse-ear chickweed (Cerastium virgatum)* | Perennial |

| Pennsylvania smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum) | Summer Annual |

| Yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) | Perennial |

*Found in multiple categories.

Drought-Prone Soils

The soil’s ability to retain water dictates how, and at what pace, water moves through the soil. A drought-prone soil is a soil in which water moves quickly though the soil profile. The composition and texture of the soil (e.g., sand, silt, or clay) influences the soil’s ability to hold water. Soils high in clay, silt, and organic matter hold water more readily than others. Soils that are sandy or low in organic matter are more prone to drought, drying out quickly (within a few days) when evaporation and transpiration rates are high due to heat, dry air, and wind.

- A soil in good health has a higher capacity to retain water for optimal lengths of time for healthy plant growth. Soil management practices that improve soil quality and enable plants to tolerate periods of drought include:

- Add organic matter to the soil, such as leaf mulch and compost. Among other benefits, organic material will encourage beneficial microbial activity, which improves rainwater infiltration and root development. The amount of organic matter applied should be determined based on soil test results, to ensure that nutrients, especially phosphorus, are not overloaded.

- Maintain soil pH at the appropriate level for the plants being grown.

- When plants are grown in soil with inappropriate pH levels, root growth is restricted. Plants with a smaller root system are unable to access available water that is lower in the soil profile

- Control erosion by ensuring that soil is covered by mulch or plants at all times. For example, grow cover crops or mulch bare soil in vegetable gardens overwinter. Under tree canopies, reduce bare soil with appropriate groundcover plants, such as white wood aster (Eurybia divaricata).

- Potassium nutrition is closely linked to soil’s ability to retain water. Optimum levels of potassium supplied in the soil improve plants’ ability to withstand drought stress (Heckman).

- Alleviate soil compaction, which negatively impacts soil quality and limits root growth.

- Avoid heavy foot or vehicle traffic on areas where plant growth is desired.

Drought-loving weeds:

USE THESE WEEDS TO IDENTIFY DROUGHT-PRONE SOILS:

| Common Name (Botanical Name) | Life Cycle |

| Black medic (Medicago lupulina) | Summer Annual |

| Crabgrass (Digitaria spp.) | Summer Annual |

| Goosegrass (Eleusine indica)* | Summer Annual |

| Plantain (Plantago spp.)* | Perennial |

| Silver cinquefoil (Potentilla argentea)* | Perennial |

| Prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare)* | Summer Annual |

| Red (sheep) sorrel (Rumex acetosella)* | Perennial |

| Spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata)* | Summer Annual |

| White clover (Trifolium repens)* | Perennial |

| Virginia pepperweed (Lepidium virginicum) | Perennial |

| Woodsorrel (Oxalis stricta) | Perennial |

*Found in multiple categories.

Compacted Soils

Soil can become compacted from excessive foot or vehicular traffic, or if the soil is cultivated when wet. Soil particles are pressed together, leaving too little space for oxygen, which is necessary for healthy root development of plants. Water struggles both to infiltrate and drain from heavily compacted soils, increasing erosion and flooding. Root growth is then stunted, due to reduced water and nutrient uptake, resulting in drought-stressed, disease-prone plants.

To correct a landscape area that has compacted soil:

- For newly planted or renovated areas: plant a cover crop, such as sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis), which replenishes nitrogen levels in the soil and has deep tap roots that help break up the soil and prevent weeds. Till under in the flowering stage before it produces seed.

- In areas with existing plants that cannot be easily removed for renovation: add compost (base quantity on soil test results). Till in only if necessary and only when the soil is dry. Rejuvenation of the area will be slow.

- Limit and re-direct foot and vehicle traffic in planted areas.

- Cultivate with a core aerator to improve oxygen movement within the soil and to encourage root growth of landscape plants.

USE THESE WEEDS TO IDENTIFY COMPACTED SOILS:

| Common Name (Botanical Name) | Life Cycle |

| Annual bluegrass (Poa annua)* | Winter Annual |

| Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis)* | Perennial |

| Broadleaf plantain (Plantago major)* | Perennial |

| Common chickweed (Stellaria media)* | Winter Annual |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | Perennial |

| Corn speedwell (Veronica arvensis) | Winter Annual |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | Perennial |

| Goosegrass (Eleusine indica)* | Summer Annual |

| Mouse-ear chickweed (Cerastium virgatum)* | Perennial |

| Path rush (Juncus tenuis) | Perennial |

| Prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare)* | Summer Annual |

| Spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata)* | Summer Annual |

| Wild garlic (Allium vineale) | Perennial |

*Found in multiple categories.

Please note:

While the consistent presence of some weeds found in specific locations can be a useful indicator as a soil health diagnostic tool, most weeds are found to grow in a variety of conditions. It cannot be assumed that a given condition exists based solely on the presence of a specific weed. For best results, take a soil test before amending any soil. For instructions, visit soiltest.uconn.edu/sampling or call the UConn Soil testing lab at (860) 486-4274 or the UConn Home and Garden Education Center toll-free at (877) 486-6271.

Other notable indicator weeds:

| Heavy shade

*See “Indicator Weeds of Turfgrass Areas” for a list of plants that thrive in shade. |

Algae, annual bluegrass (Poa annua), common chickweed (Stellaria media), ground ivy* (Glechoma hederacea), Japanese stiltgrass* (Microstegium vimineum), mouse-ear chickweed (Cerastium virgatum), moss, nimblewill (Muhlenbergia schreberi), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), violets (Viola spp.) *CT Invasive. |

| High fertility | Common chickweed (Stellaria media), creeping bentgrass (Agrostis palustris), lambsquarters (Chenopodium album), pigweed (Amaranthus spp.), pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), wild carrot (Daucus carota), velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) |

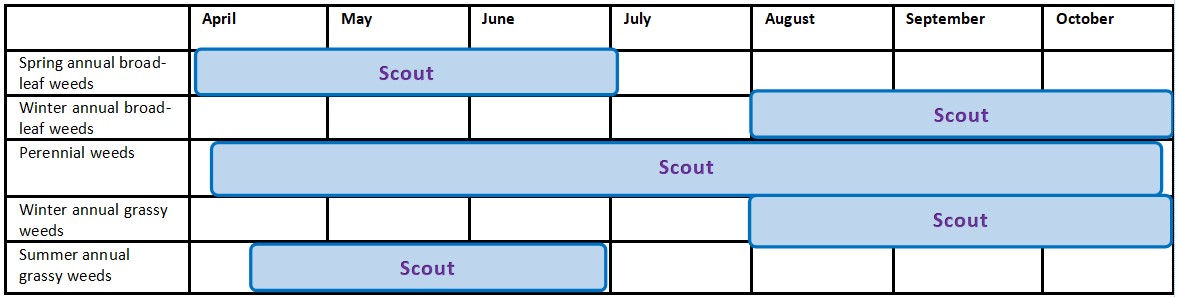

Weed Scouting Calendar:

Glossary:

Annual: a plant that completes its life cycle from seed to mature plant in one year. Winter annuals complete their life cycles from fall to spring. Summer annuals complete their life cycle from spring to fall.

Biennial: a plant that completes its life cycle in two years. Flowering and seed production occur in the second year.

Integrated Pest Management: IPM is a sustainable and scientific approach to pest control that strives to address and correct the root causes of weed problems rather than just the symptoms. Multiple techniques (e.g., cultural, mechanical, chemical, biological) are employed for an overall strategy that is effective, economical, and ecologically sustainable.

Perennial: a plant that lives more than two years and continues growing until it reaches maturity (3-5 years on average).

Bibliography:

- Charbonneau, P. & Hsiang, T. (2015). Integrated Pest Management for Turf. Ontario, Canada: Ministry for Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. omafra.gov.on.ca

- Kujawski, J. (2011). Managing Soil Structure for Water Conservation in the Landscape. UMass Extension. ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets

- Danko,L. (2014). Rain Gardens - the Plants. PennState Extension. extension.psu.edu/rain-gardens-the-plants

- Voyle, G. & Hudson, H. (2014). What to do about compacted soil. MSU Extension. msue.anr.msu.edu/news

- The Lawn Institute. (n.d.). Weeds are Indicators of Soil Problems. toddvalleyfarms.com

- Derr, J. F. (2000). Weeds as Indicators of Environmental Conditions. Michigan State University. lib.msu.edu

- Botts, B. (n.d.). The Language of Weeds. Chicago Botanical Garden. chicagobotanic.org/plantinfo

- Kujawski, R. (2011). Long-term Drought Effects on Trees and Shrubs. UMass Extension. ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets

Photos by Alyssa Siegel-Miles unless otherwise specified.

Questions? Contact:

Vickie Wallace

UConn Extension

Extension Educator

Sustainable Turf and Landscape

Phone: (860) 885-2826

Email: victoria.wallace@uconn.edu

Web: ipm.uconn.edu/school

©UConn Extension. All rights reserved.

Updated March 2018