Authors

Tina Smith (retired)

Extension Educator

UMass Extension Greenhouse Crops and Floriculture Program

Introduction

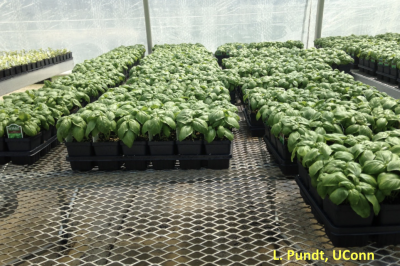

Commercial herb bedding plant production is increasing and with it, a recognition that disease and insect pests can adversely affect their market quality. Herbs can be marketed for their culinary, fragrance, medicinal and ornamental uses. However, they are a minor or specialty food crop and there are few pesticides registered for use on them. The laws controlling the use of pesticides are stricter for food crops than for ornamentals. A review of pesticide labels indicates only a limited number of insecticides and fungicides are labeled specifically for herbs grown in greenhouses. In addition, no plant growth regulators are labeled for use on herbs. The maximum safe amount of residues, known as tolerances, must be set for every food use before a pesticide is registered. If the "days to harvest" (the minimum number of days between the last pesticide application and harvest) are followed, the residue on the crop should be below the tolerance level. Most herbs are "herbs and spices" but a few, such as parsley, may be considered "leafy vegetables."

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) offers a practical way to effectively manage pests on herbs. High quality herbs can be grown by using regular monitoring, accurate problem identification, sound cultural practices, and timely implementation and evaluation of appropriate management strategies. IPM brings together all available management options including cultural, physical, mechanical, biological, and chemical tactics. Regular monitoring can alert growers to developing pest and cultural problems while they are still minor and more easily managed.

To begin, obtain up-to-date cultural information and schedules for producing herbs as bedding plants. Many herbs are native to regions with soils that are neutral to slightly alkaline. They grow best in a very well drained growing media with a pH range of 6.0 to 7.0 but tolerate pH outside of this range.

Herbs generally prefer a drier growing media and lower fertility levels than do bedding plants. Drier growing conditions help prevent diseases such as root rots and Botrytis. Some herbs, however, such as basil, parsley, and a few mints, prefer moist conditions. Proper scheduling, spacing and sufficient light levels are needed to avoid leggy, overgrown herbs. If started to early, fast growing herbs can easily become overgrown. Most herbs can be grown at the same temperatures as bedding plants: 70 to 75 °F day temperatures and 60 °F night temperatures.

Insect and Mite Pest Management

A regular monitoring program is the basis of all pest management programs. Establish a monitoring and record-keeping system for all crop production areas including stock plants, propagation areas and outdoor yards.

Before starting a biological control program, develop regular, consistent scouting protocols. This helps you anticipate when the various pests will be of concern, so you can plan to release the biological control agents (BCAs) in sufficient time. You will also know where potential hot spots of pest activity are and can evaluate the effectiveness of the biological control agents (just as you evaluate the effectiveness of any method of control).

A regular, routine scouting program that consists of the use of sticky cards, random plant inspections and using key indicator plants to detect problems early (See table 1). Early detection of pests, when plant canopies are still small, results in better spray coverage and better pest control. With limited pesticides available for use on herbs, spray applications need to be as effective as possible. Use a sprayer that can generate a very fine droplet size. Many insecticides registered for use on herbs work by contact, so achieving good spray coverage is essential to obtaining good control. Water-sensitive cards can be used to determine your spray coverage. BCAs are not available for all pests, so pesticide use may still part of an IPM program for herbs.

Insect screening can be used to exclude insects from the greenhouse, especially from propagation areas. Before installing screening, determine which insects you need to exclude and how to use the screening. Insect screening is only effective if the screened area is the only access point for insects. Proper design is needed for adequate ventilation. If improperly designed, the fans may become overheated.

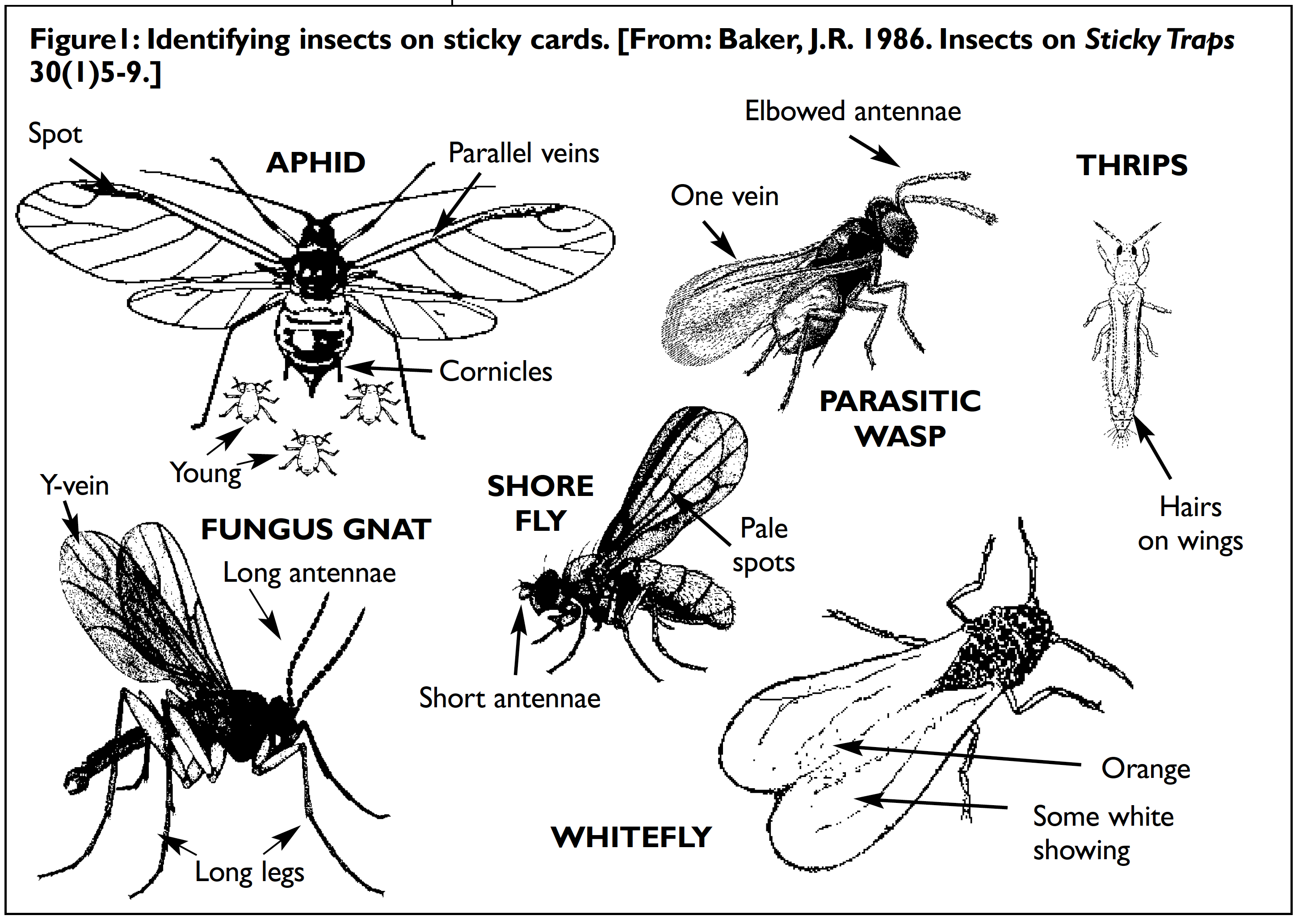

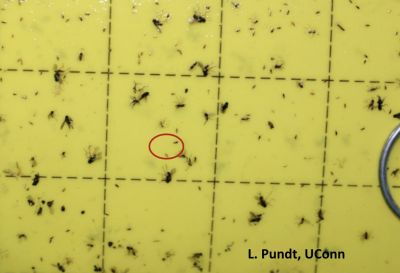

Sticky Cards

Use yellow sticky cards to detect adult whiteflies, aphids, thrips, fungus gnats and shore flies. Place 1 to 4 cards per 1000 square feet. Space cards equally throughout the greenhouse in a grid pattern, with additional cards placed near doorways and vents. Inspect cards each week, identifying and counting the insects. Record the information on a scouting form (forms are available at the UConn IPM Web site at https://ipm.cahnr.uconn.edu/greenhouse/. Replace the cards weekly to keep track of population trends. In crops that are especially prone to thrips, you may consider using blue sticky cards which are more attractive to thrips than the yellow sticky cards.

Yellow sticky cards will attract many parasitic wasps and other flying BCAs, so reduce the number of sticky cards used or wait a few days after your biological control releases before putting the sticky cards in place. Focus more on plant inspections to evaluate the effectiveness of your IPM program.

Plant Inspection

In greenhouses and outdoor production areas, plant inspection is needed to detect cultural problems and diseases, and to assess general plant health. Plant inspection is also needed to detect aphids, fungus gnat and thrips larvae, immature whiteflies, and spider mites. Use a 10 to 20x hand lens or hands-free magnifier (Optivisor™) to identify these key pests and their life stage. When scouting, avoid wearing light colors (especially yellow), so insects are not attracted and then carried on clothing from one area to another. Based upon your scouting records, monitor least infested areas first and the most heavily infested areas last. Examine stock plants before cuttings to reduce the possibility of infesting the stock plants. When stock plants are held at lower temperatures, insects are less active, so plant inspections are more important than sticky card counts during the winter months.

Randomly select plants at 10 locations in an area of 1000 square feet, examining plants on each side of the aisle. Start this pattern at a slightly different location each week, walking through the greenhouse in a zigzag pattern down the aisles. Look on the undersides of leaves for insects and mites and inspect root systems. Become familiar with key plants and their associated pests so you know which insects and diseases are most likely to cause problems. Key plants are those herbs most likely to have pest problems (See table 1).

Record-keeping and decision-making

Each time the crop is scouted, record pest numbers and location and number of plants inspected. This helps you identify population trends and indicates if initial control measures were successful or if they need to be repeated.

Biological Control Agents for Insects and Mites

Biological control is the use of living organisms or biological control agents (BCAs) such as host specific parasitic wasps, predators, pathogens and entomopathogenic nematodes. BCAs are best used preventively combined with proper cultural controls and sanitation practices. Commitment, patience, and a desire to learn about the biology and life cycles of the pests and their natural enemies are all needed.

Before releasing biological control agents, you need to have a regular scouting program established. Natural enemies, especially parasites, are often specific to a pest or may be shipped in a stage that does not attack the targeted pest.

Start planning your biological control program six months to one year in advance. Develop a spread sheet with the dates of when your cuttings and plugs arrive, and when your greenhouses will be open for production. This will help you pre-order the biological control agents from your suppliers. You can order additional natural enemies if hot spots develop. Work with your suppliers to decide if a regular standing order is needed or whether a week by week order is needed. In general, shipments of BCAs should be received within 4 days after placing an order and kept cool during shipment. Inspect the BCAs for viability and quality when they are received. Most BCAs should be released immediately upon arrival.

Research in biological control is ongoing, so check with your university specialist on new developments before beginning a program. Work with your supplier and university specialist to determine specific release rates and timing. Become familiar with the environmental conditions needed by the natural enemies when they are released in the greenhouse.

A frequent question from growers is whether pesticides can be used with biological control agents. For some pests, effective biological control agents are not yet available. New or secondary pests may suddenly appear or be introduced on plant material and still need to be managed. Pesticides have direct effect killing the natural enemy or cause their non-emergence from eggs or pupae. Pesticides may also indirectly affect the ability of the BCAs to survive and reproduce. Many insecticide residues can adversely affect natural enemies for up to three months after their application.

Some alternative pest control materials may be more selective and less harmful to certain natural enemies. Microbial biopesticides may be compatible with some, but not all BCAs. For example, Beauveria bassiana (BotaniGard WP) sprays are considered “generally safe” against the predatory mites, Neoseiulus cucumeris and Amblyseius swirskii but are not compatible with the minute predatory bug, Orius sp.

The major suppliers of BCAs such as Koppert, Biobest, and Bioline Agrosciences have developed online side effects databases or downloadable apps that can provide more information. Bioworks also has additional online resources. Check with your biological control suppliers for more information.

Specific Insect Pests and Mites

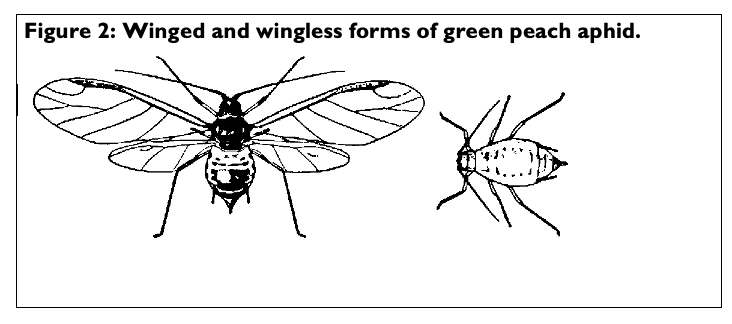

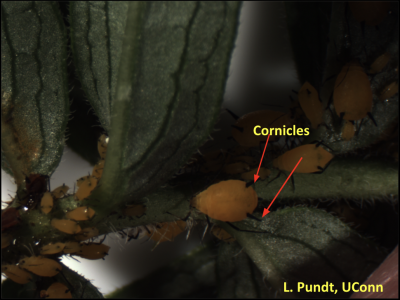

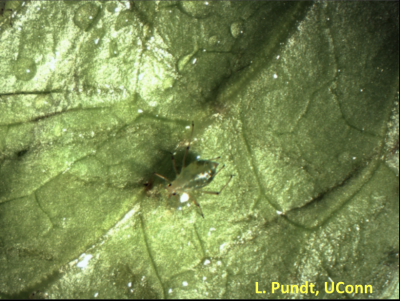

Aphids

Aphids are small (less than 1/8 of an inch long) soft-bodied insects, with piercing-sucking mouth parts. Green peach (Myzus persicae), melon/cotton (Aphis gossypii) and foxglove (Aulacorthum solani) aphids are commonly found in the greenhouse. Many herbs, including lemon verbena, curry plant, rosemary, oregano, lemon balm, dill, basil, lavender, mint, thyme, sage, and rue are susceptible to aphids. Look for wingless aphids on the young, tender growth. Signs of aphid infestation include whitish, cast skins, honeydew, and sooty mold. The foxglove aphid may cause more leaf distortion on tender new growth than the green peach aphid. Winged aphids appear when the colony becomes overcrowded or when they migrate to new hosts.

Aphids give birth to live young (100 to 200 nymphs) in the greenhouse. They can, in turn, give birth to young in as little as 7 to 10 days. Therefore, populations can increase rapidly. Aphids may enter greenhouses on incoming plants, on worker's clothing or through vents. Weeds are often an overlooked source of continuing aphid infestations.

Management:

- Eliminate weeds.

- Inspect incoming plants for signs of aphids.

- Avoid over-fertilizing plants, especially with nitrogen.

- Use labeled insecticides. Repeat applications are often needed.

- Use biological control agents.

Several different biological control agents are commercially available for greenhouse use including host specific parasitoids and more generalist predators.

Scouting for Aphids

- Yellow sticky cards will only trap winged adults, visual inspection is needed.

- Wide host range. Look for wingless aphids on the young tender growth of basil, curry plant, dill, lavender, lemon balm, lemon verbena, mint, oregano, rosemary, rue, sage, thyme ...

- White, cast skins, shiny honeydew, sooty mold and the presence of ants are signs of aphids.

- When releasing host specific parasitic wasps, identification to species is needed.

Aphid Parasitoids

There are several host specific parasitic wasps that can be released preventively. These small parasitic wasps lay their eggs inside the aphid. The aphid is killed as the developing larvae first feed upon it and then spin their cocoons. The brown, swollen exoskeleton of the aphid remains, known as a “aphid mummy”, that resembles a sesame seed with small, round exit holes where the parasitic wasp emerged. Parasitic wasp adults feed on nectar and honeydew. Avoid releases of these parasitic wasps near yellow sticky cards for they will be trapped on the cards. Do not release in bright sunlight, as they will get trapped in any condensation on the glazing. Aphidius colemanii attacks smaller aphids such as the green peach and melon aphids. Aphidius matricariae attacks green peach aphids. Aphidius ervi attacks larger aphids such as the foxglove aphid. Mixtures of parasitic wasps are also commercially available and can be used when multiple aphid species are present. Aphelinus abdominalis also attacks the foxglove aphid.

Aphid Predators

A predatory midge, Aphidoletes aphidimyza, is sold in the pupal stage in bottles or blister packs. The short-lived adults are rarely seen, as they search for aphids at night. The bright orange larvae kill aphids by biting their knee joints, injecting a paralyzing toxin, and sucking out body fluids. The larvae drop to the ground to pupate, so peat or holes in the weed mat barrier are helpful, but not essential to provide pupation sites. Aphid midges complete their life cycle from egg to adult in 3 to 4 weeks. They are most effective in the summer and will go into a diapause (dormant period) during cool, short days unless supplemental lighting is provided.

The green lacewing, Chrysoperla rufilabris, can be purchased in the egg or larval stage. Adults feed on nectar, pollen, and honeydew. Lacewing larvae (also known as aphid lions) prefer to feed on aphids but also feed upon spider mites, thrips, and whiteflies. Aphid lions, which grow to 1/2-inch-long, are light-colored and mottled, with large sickle-shaped mouthparts. Lacewings can also feed upon each other, so they must be released as far apart as possible to discourage cannibalism. Their life cycle from egg to adult takes about 4 weeks.

The convergent lady beetle, Hippodamia convergens, feeds upon many different types of aphids and other soft-bodied insects. Eggs are laid near abundant prey. Their life cycle from egg to adult takes about 4 weeks. Ladybird beetles will not establish in the greenhouse. Continued releases every 3 to 4 days are needed to assure coverage over time.

In display beds outdoors, natural enemies, including ladybird beetles, lacewings, flower flies (also known as hover flies) and naturally occurring fungal diseases also help to manage aphid populations.

Entomopathogenic Fungi

Beauveria bassiana is an insect-killing fungus that can be used at the first sign of aphids. Repeat applications are needed to contact those aphids that may have shed their skins before becoming infected by the fungus. Isaria fumosoroseus is another insect killing fungus that is commercially available.

Beetles

Beetles are a large group of insects in which both adults and larvae have chewing mouth parts. Herbs grown outdoors are especially prone to beetle damage.

Early in the growing season, flea beetles can injury some types of herb seedlings. Adults overwinter in leaf litter and emerge from late April to early May. Look for small adult flea beetles feeding on plants early in the season, perforating foliage with tiny shot holes. They characteristically jump when disturbed.

Asiatic garden beetle (Maladera castanea) is a 1/2-inch-long, rounded, chestnut-brown beetle which is active from late spring through mid-summer. They feed at night and hide during the day in the soil or debris around the base of plants. Asiatic garden beetles are sometimes attracted to porch lights at night. Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) are familiar to nearly everyone as a brown and metallic-green species active in the daytime during the summer. Basil is one of the favored hosts for both beetle pests.

Management

Some species of entomopathogenic nematodes (Heterorhabditis bacteriophora) are used against certain scarab grub species. Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. galleriae (SDS-502 strain) is labeled for Japanese beetle control on herbs. Screening or row covers can be used in outdoor beds.

Caterpillars

Many different types of caterpillars, including cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni), imported cabbageworm (Pieris rapae) and black cutworm (Agrostis ipsilon) may occasionally feed upon herbs. Winged moths or butterflies may enter greenhouses through openings and lay eggs on plant foliage. The eggs hatch into caterpillars that feed on herbs with their chewing mouthparts.

When inspecting foliage, look for bites taken out of leaves and droppings left behind by caterpillars. Cutworms can be found at the base of the plant during the day. Other cutworm species can often be found hanging from the underside of the leaf.

Management

- Eliminate weeds that may serve as alternate hosts.

- Clean up plant debris that may harbor overwintering pupae.

- Install insect screening to prevent entry of adults into the greenhouses

- Use labeled insecticides.

- Use biological control agents.

The commercially available egg parasitoid, Trichogramma spp. lay their lay their eggs into the eggs of caterpillar pests such as the diamondback moth, cabbage looper and imported cabbageworms. These mini wasps have a rapid life cycle of about 7 to 10 days from egg to adult, so populations can increase rapidly. Timing is critical as these very small wasps only work against the egg stage and not the larval stage. Trichogramma turns the eggs of some caterpillars black. When releasing these mini wasps, protect them from ants.

The insect pathogen, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (Bt) can be used against many different species of caterpillars. It is most effective against young, actively feeding caterpillars. BT is a stomach poison so must be ingested to be effective. It breaks down when it is exposed to sunlight, so is best applied in the evening or early morning hours. Test the pH of your spray water, it should be 7.0 or less, as high pH water can reduce its effectiveness. Add a spreader sticker to the tank mix to improve the effectiveness of your spray. Repeated applications are needed.

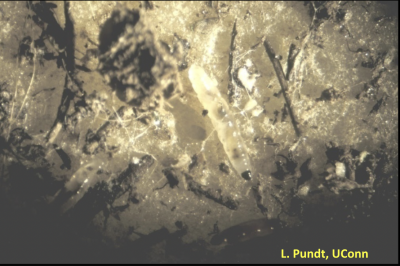

Fungus Gnats

The moist greenhouse environment favors fungus gnats (Bradysia spp.), that are common pests in propagation areas. Adult fungus gnats are small (1/8 of an inch long), mosquito-like flies with long legs and antennae. They are often confused with the shore flies that feed upon algae growing in moist areas in the greenhouse.

Female fungus gnats lay up to 200 eggs in the upper surface of moist growing media. Eggs develop into translucent legless larvae with shiny black heads. Fungus gnat larvae feed upon the developing callus of young cuttings, delaying rooting. They also feed upon young roots and cause wilting and plant death. Their life cycle from egg to adult takes 3 to 4 weeks. Overlapping generations often occur in the greenhouse.

Monitor for adult fungus gnats by placing yellow sticky cards at the media surface at the base of plants. Monitor for larvae by placing raw, peeled potato chunks on the growing media surface and checking every two days for the larvae.

Inspect incoming plugs for fungus gnat larvae. Recent studies have shown that fungus gnats may be introduced into a greenhouse from soilless media or on rooted plant plugs. Adults are attracted to mixes with high microbial activity, or with high amounts of peat moss or compost or composted hardwood bark. Avoid using mixes with immature composts less than one year old. However, no potting mix is immune to fungus gnat infestations

Management

- Use proper watering techniques. Avoid overwatering, which contributes to high moisture levels in the potting media as well as to puddling on the floor.

- Store media in a dry location.

- Keep floor as dry and weed-free as possible.

- Remove plant debris, weeds, and old growing media from inside and outside the greenhouse.

- Inspect incoming plugs for fungus gnat larvae or their feeding damage.

- Use biological control agents against the fungus gnat larvae.

- Use labeled insecticides.

Several biological control agents are available. Entomopathogenic (insect-killing) nematodes (Steinernema feltiae) can be applied as a soil drench or sprench against fungus gnat larvae. These beneficial nematodes enter the insect's body through openings in their exoskeleton. The nematodes multiply inside the host and release a bacterium that is toxic to the host insect. They reproduce within the fungus gnat larvae, exit the dead body, and will search for new hosts to infect. Repeated applications are often needed. Test nematodes for viability before applications.

Rove beetle (Dalotia coriaria) is a generalist predatory beetle. Both adults and larvae feed upon fungus gnat eggs and larvae. Rove beetles are strong fliers and their flights often occur at night. Rove beetles hide in cracks and crevices in the growing media so may be difficult to detect when scouting.

Stratiolaelaps scimitus is a generalist predatory mite that feeds upon fungus gnat larvae, thrips pupae and shore fly larvae. S. scimitus is a scavenger that can survive in the absence of fungus gnats on plant debris and algae. It may take several weeks for these predatory mites to reach an effective level, so they are often used in conjunction with either insect-killing nematodes or rove beetles.

Hunter flies (Coenosia attenuate) are not commercially available but may be introduced on incoming plant material. These aerial predators will catch fungus gnats or shore fly adults on the wing. They are about twice the size of shore flies. Hunter flies also have wings that are clear and may appear iridescent as the adults’ perch on plant leaves, pipes, or other objects in full sun. The female has a dark gray body with black legs while the male has yellow legs. Adults lay their eggs in the growing media and their larvae prey upon fungus gnat larvae in the growing media.

Scouting for Fungus Gnats

- Use yellow sticky cards (horizontal placement is best or vertical placement near growing media to attract winged adults).

- Use potato chunks or slices to monitor for larvae. Check after two days.

- Look for larval feeding damage on young seedlings in propagation houses.

- Fungus gnats have a wide host range and are favored by moist habitats.

Plant Bugs

Four-lined (Poecilocapsus lineatus) and tarnished plant bugs (Lygus lineolaris) are common on herbs grown outdoors and may enter greenhouses through vents, especially from weedy outdoor areas. Four-lined plant bugs are 1/4 of an inch long, yellow or greenish in color with 4 characteristic black lines and are commonly found on mints. Feeding damage results in leaves with brown, dead spots that are often confused with a fungal leaf spot disease. Four-lined plant bugs are timid insects and hide under leaves when disturbed.

Tarnished plant bugs are 1/5 of an inch long and bronze in color with yellow and black dashes. Adults and nymphs feed on plant sap using long sucking mouth parts. They also inject a toxin that causes death of the tissue. Symptoms may include death of tender young growth, dead spots, and badly distorted buds. The life cycle from egg to adult takes 3 to 4 weeks.

Monitor feeding damage through routine plant inspections. Management includes removal of trash, debris, and weeds from production areas, and treating plants with a labeled insecticide.

Leafhoppers

The sage (also known as mint) leafhopper feeds upon herbs in the mint family, such as rosemary, sage, catnip, spearmint, lavender, and oregano. Native to Europe, this leafhopper is now established in the United States. It has been reported to be a pest both outdoors and in greenhouses. Adults are small (slightly larger than 1/8-inch-long) and pale with distinctive brownish oval markings. Their feeding damage may be confused with damage caused by thrips, lacebugs or spider mites.

Management

Leafhoppers are notoriously difficult to control because they are so active and mobile. Unfortunately, using contact insecticides which are labeled for use on herbs, have limited efficacy, since new leafhoppers can enter an area after the sprays have dried.

Leafhoppers natural enemies include lady beetles, lacewings, spiders, and damsel bugs. Unfortunately, these natural enemies usually do not provide adequate control. Proper use of insect screening can help keep leafhoppers out of greenhouse production areas.

Leafhoppers

- Slender insects with short bristle like antennae.

- Wings are held roof like over the abdomen.

- Wedge shaped, tapering to the rear.

- No antennae visible.

- Color vary depending upon species.

from thrips, or spider mites.

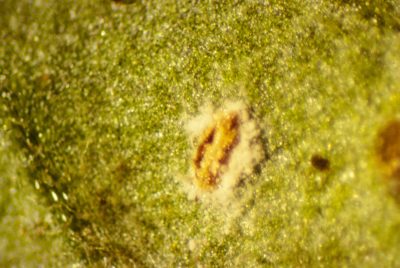

Mealybugs

Mealybugs may be occasional pests of herbs especially on plants that are overwintered or carried over from season to season or herbs propagated by cuttings. They usually enter a greenhouse on infested plant material. Both adults and crawlers feed upon herbs causing stunting, leaf yellowing and plant distortion. Honeydew and sooty mold are unsightly.

Mealybugs are small, oval, soft bodied insects covered with a white, cottony wax-like layer. They can affect all parts of the plants and some species even feed upon the roots.

Early detection of mealybugs is difficult but is needed to avoid outbreaks. As only the short-lived winged males fly, do not rely on yellow sticky cards to detect mealybugs. Early infestations can be easily overlooked due to the mealybug's tendency to hide in protected locations. Mealybugs can be difficult to find if populations are low. Look for white flecks or cottony residues along the leaf midribs, on leaf or stem axils, stem tips and on the underside of leaves and near the base of plants. Honeydew, sooty mold, and the presence of ants may also be an indication of a mealybug infestation.

Management

- Inspect incoming plants for signs of mealybugs.

- Keep plants well-watered and do not overfeed them. High nitrogen fertility favors mealybug reproduction.

- Keep greenhouses as weed free as possible and do not overwinter pet plants that may become infested with mealybugs.

- A forceful jet of high-pressure water twice a week may help remove mealybug eggs, crawlers, and adults.

- Immediately dispose of heavily infested plants and do not reuse contaminated pots.

- Power wash and sanitize greenhouse benches between crops.

- Bait ants that can move crawlers around and disrupt biological controls.

- Destroy heavily infested plants.

- Use labeled insecticides.

- Use biological control agents.

The mealybug destroyer, (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri) is commercially available as adults and larvae that prey on all stages of mealybugs. It reproduces on mealybugs that produce egg masses, such as the citrus mealybug. This predatory beetle prefers warm temperatures above 60° F. Release in the evening and place in distribution boxes in the plant canopy. The host specific parasitic wasp (Anagyrus pseudococci), parasitizes citrus mealybug larvae.

Scouting for Mealybugs

- Look for white flecks or cottony residues along leaf midribs, on leaf or stem axils, and underside of leaves.

- Some key hosts include jasmine and scented geraniums.

- Shiny honeydew, black sooty mold fungus and the presence of ants are signs of mealybugs.

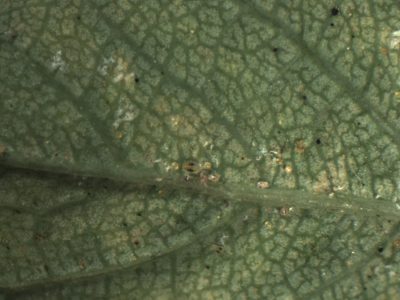

Mites

Two-spotted spider mites

Adult female two-spotted spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) are approximately 1/50 of an inch long and green to slightly orange in color. When mature, they have two dark spots on either side of their bodies. Their life cycle from egg to adult can be completed in as little as 7 days at temperatures greater than 85°F. Females may lay up to 100 eggs during their 3 to 4-week lifespan.

Spider mites have piercing mouthparts. As they feed, chlorophyll is removed, and leaves become flecked or stippled or bronzed. Leaves may also turn yellow and drop, and webbing may be seen when outbreaks occur. Many herbs are susceptible to spider mites including lemon balm, lemon verbena, lemon grass, mint, pineapple sage, sage, and oregano. Scout for mites and signs of their damage in hot, dry areas of a greenhouse. A 10 to 20x hand lens is necessary to see the eggs, nymphs, and adults of the spider mites. Turn leaves over and look for the mites along the leaf veins.

Management

- Inspect incoming plants for signs of spider mites or their damage.

- Avoid over fertilizing plants. Spider mites are more able to feed upon lush, succulent growth. Increased fertility levels, especially nitrogen, provide amino acids that are needed for the spider mites to develop.

- Eliminate weeds in and around greenhouses.

- Avoid allowing plants to become water stressed, as those plants have higher levels of amino acids, which are favorable to spider mites. Overhead watering both helps wash spider mites off plants and increases relative humidity in the plant canopy

- Use labeled miticides. Many of the miticides labeled for herbs work by contact and have no residual activity. Follow-up inspections are needed to determine if repeat treatments are needed. When using contact materials, be sure to obtain good coverage to the undersides of the leaves.

- Use biological control agents.

Predatory mites, predatory midges and predatory beetles can all be used in a biological control program. Different species of predatory mites (Phytoseiulus persimilis), Neoseiulus (Amblyseius) californicus, Amblyseius andersoni, Galendromus occidentalis, Mesoseiulus longipes, and Neoseiulus (Amblyseius) fallacis are each adapted to different environmental conditions (temperature and relative humidity levels).

The widely used and effective predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis feeds on all stages of two-spotted spider mites. The adult P. persimilis is bright red in color, pear-shaped, long-legged, slightly larger, and more active than spider mites. Adult females lay eggs that are about 2 to 3x the size of two-spotted spider mite eggs and are more “football” shaped than the round spider mite eggs. Look for the eggs to be sure the beneficial predatory mites are reproducing

P. persimilis is a specialist predatory mite that can only survive by feeding upon two-spotted spider mites. When shipped as adults in bottles, it is important to order them from producers with overnight shipping and delivery.

However, with the recent (2021) development of a new alternative food system for rearing P. persimilis, slow release sachets of this predatory mite species are now commercially available. These sachets contain all stages of the predatory mites (adults, nymphs, and eggs) for longer prevention and higher egg laying ability.

A tiny predatory midge larva, Feltiella acarisuga, also feeds on two-spotted spider mites. This midge prefers humid conditions and can forage on hairy leaves. It is commercially shipped in the pupal stage and hatches into midge adults on arrival. Adults lay eggs near spider mite infestations. Because the adults can fly, they can locate spider mite populations not readily accessible to predatory mites.

A small, black predatory lady beetle, Stethorus punctillum, feeds on all stages of spider mites. Because the adults can fly, they can locate spider mite populations not readily accessible to predatory mites.

Scouting for Spider Mites

- Visual inspection is needed as the wingless mites will not be found on sticky cards.

- Wide host range. Look on underside of leaves, along the leaf vein on lavender, lemon balm, lemon grass, lemon verbena, mint, oregano, pineapple sage, sage….

- Especially near hot, dry areas of a greenhouse.

Scale Insects

One of the more common types of scale insects found in greenhouses is the brown soft scale, Coccus hesperidum. Adult females are oval, 1/10 of an inch long, yellowish brown when young and becoming darker brown as they age. Crawlers are yellow and flat. Scale insects are often found along the veins and on the stem. Brown soft scale can produce large amounts of honeydew, resulting in the growth of sooty mold. This scale may be found on sweet bay (Laurus nobilis).

Inspect incoming plants for scale insects with a 20-30x hand lens. Look on the upper and lower leaf surfaces, leaf axils, bud, and stems. For soft scales, look for honeydew, and black sooty mold. Ants and wasps may also be attracted to the honeydew. Soft scales appear convex in shape resembling a helmet. Hard scales are harder to detect because they do not produce honeydew. They produce a waxy covering called a test, which protects adult females, as well as eggs and crawlers from natural enemies. Armored scales are circular or rounded in shape.

It is important to know if the scale insect is alive or dead. Use a small needle or sharp fingernail to see if you can pop off the scale cover. Look for a pink or orange-bodied scale insect. If the scale is dead, the body will be dry and shriveled or absent. If when you probe the insect, and you see a colored liquid, they are alive. When you crush them, if there is no liquid, they are dead.

Management

- Inspect incoming plants for scale insects.

- Remove heavily infested plants and do not overwinter pet plants infested with scale insects.

- Prune out heavily infested branches.

- Avoid over-fertilizing especially with nitrogen, as this encourages the development and reproduction of scales.

- Use labeled insecticides.

The immature crawler stage is the most susceptible stage to insecticides. However, there are overlapping generations in the greenhouse, so repeated applications are needed as not all the eggs hatch at once.

Shore Flies

Adult shore flies are 1/8 of an inch long, robust, with short legs and antennae and 5 light spots on their wings. Shore flies are primarily an annoyance and are not believed to cause direct plant damage. They are best managed by controlling algae, their food sources.

Thrips

Thrips are small and tend to feed in plant buds and flowers, so considerable damage can occur before they are detected. The most common and destructive thrips species in greenhouses is the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis). This species also transmits tospoviruses (impatiens necrotic spot virus and tomato spotted wilt virus). Adults are about 1/16 of an inch long with narrow bodies and fringed wings. The small yellow larvae can be found on the foliage. Thrips feeding damage results in white scars on expanded leaves or flowers. After thrips feed within developing buds, the leaves or flowers become distorted. Many herbs including basil, French tarragon, mint, lemon grass, rosemary, sage, and thyme are susceptible to thrips.

In general, the thrips life cycle (from egg to adult) takes two to three weeks to complete. This depends upon temperature, for example, their life cycle takes 7 to 13 days at optimum temperatures between 79 - 84°F.

Use yellow or blue sticky cards to detect adult thrips. Look for feeding damage during routine foliage inspection. Tap foliage over a sheet of white paper and use a 10 to 20x hand lens to see the adult or larval thrips.

Management

- Inspect incoming plants.

- Eliminate weeds inside and outside the greenhouse. A weed free barrier of at least 10 ft around the greenhouse may help to discourage thrips entry.

- Dispose of plant debris in tightly sealed containers. Do not allow open garbage bins in the greenhouse, as thrips may disperse from the plant material unto the crop.

- Use labeled insecticides. Several insecticide treatments are suggested at 3 to 5-day intervals (depending upon temperature) using spray equipment that produces very small-diameter spray droplets which can penetrate growing points, and other areas where thrips feed. Thrips populations on cards tend to peak every 2 to 3 weeks. Apply insecticides before this peak, so the adults are killed before they lay eggs. Rotation between classes of insecticides may help to delay the development of resistance to certain insecticides.

- Use biological control agents.

Several biological control agents are commercially available. Neoseiulus cucumeris, is a small predatory mite that feeds upon the small, first instar thrips larvae. It can also feed upon pollen. N. cucumeris is sold in mini sachets on a stick containing bran and flour mites as a food source. The predatory mites emerge from the sachets over a 4-week period. Place the sachets within the plant canopy, so the sachets are shaded. Direct sunlight raises the temperatures and dries out the mini sachets, so the predatory mites do not lay as many eggs, reducing their effectiveness. These predatory mites can also be broadcasted or placed in breeding piles. The predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii, feeds upon thrips larvae, and is most effective during warmer temperatures (70°F) than N. cucumeris.

Drench applications of the insect killing beneficial nematode (S. feltiae) that is used against fungus gnat larvae can also affect thrips pupae in growing media. Start with drench applications to the growing medium followed by weekly spray or sprench applications. Apply nematodes in the early morning or late evening to avoid desiccation (from ultra-violet light).

Orius insidiosus, the minute pirate bug, attacks all stages of thrips by sucking out their body fluids. Orius also feeds upon pollen, as well as spider mites and aphids. Because minute pirate bugs may take up to 12 weeks to establish in the greenhouse, Orius may be released unto thrips banker plants or habitat plants to encourage their establishment.

The insect pathogen, Beauveria bassiana may help to suppress thrips populations. This biopesticide creates an infection as the fungal spores penetrate the host insect. Good coverage is needed to contact the thrips. Isaria fumosoroseus is another insect killing fungus that is commercially available.

Scouting for Thrips

- Yellow sticky cards are needed to detect early infestations.

- Wide host range.

- Look for thrips adults and larvae and their damage (white scarring, distorted growth, small fecal spots) especially on basil, French tarragon, lemon grass, mint, rosemary (flowers), sage, and thyme….

Whiteflies

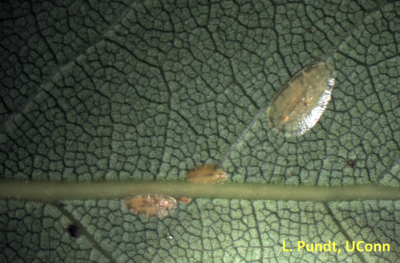

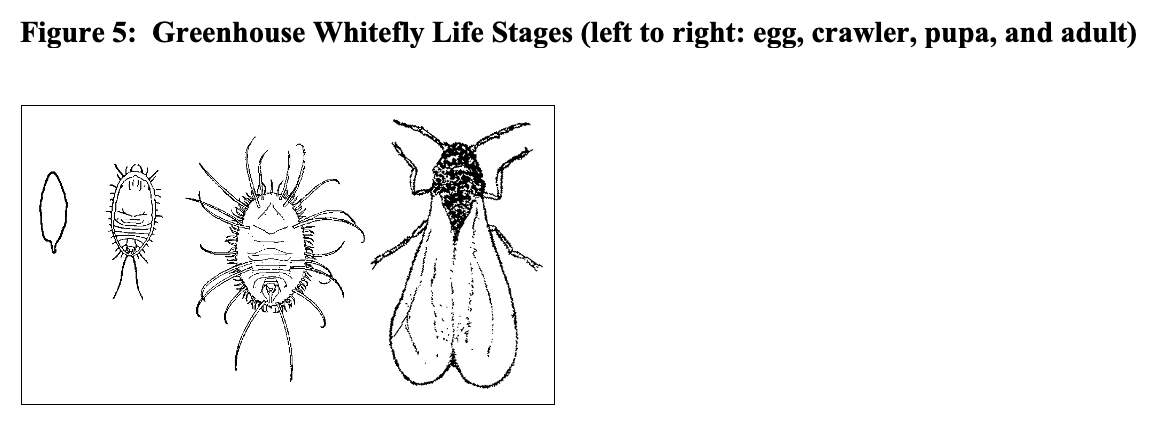

Whiteflies are powdery-white insects approximately 1/16 of an inch long with piercing-sucking mouthparts. The most common species found in greenhouses is the greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) and, to a lesser extent, the sweet-potato whitefly (Bemisia tabaci). Whiteflies may attack a wide range of herbs including mint, lavender, pineapple sage, lemon balm, rosemary, marjoram, oregano, sage, rue, scented geraniums, basil, and lemon verbena. When high populations develop, honeydew and sooty mold may be seen. Adult whiteflies lay their eggs on the tender young growth. The immature scale-like crawlers can be found on the undersides of the leaves. Their life cycle from egg to adult takes from 3 to 5 weeks depending upon greenhouse temperatures.

Monitor adult whiteflies using yellow sticky cards. Monitor immature stages found on the undersides of leaves during weekly foliage inspections.

Management

- Inspect incoming plants.

- Eliminate weeds in and around greenhouses.

- Avoid over fertilizing crops as this increase their attractiveness to adult whiteflies.

- Use labeled insecticides. Repeat applications are often needed. When using contact materials, be sure to obtain thorough coverage to the undersides of the leaves where the immature and adult stages are found.

- Use biological control agents.

Several biological control agents are commercially available. Encarsia formosa is a small, parasitic wasp that attacks both greenhouse and sweetpotato whiteflies. However, it is more effective against the greenhouse whitefly. Encarsia is generally sold as parasitized greenhouse whitefly pupae that are glued onto small cards. These cards can be hung on lower leaf petioles. Encarsia needs to be released as soon as the first whiteflies are detected, and repeated releases are often needed. The adults are especially sensitive to many different pesticide residues.

Eretmocerus eremicus is a small, lemon-yellow wasp with green eyes and clubbed antennae. It is more effective than Encarsia against the sweetpotato whitefly. Eretmocerus is native to the desert regions of Arizona and California and appears to be better adapted to high temperatures in greenhouses. Whitefly nymphs can be killed by host feeding and parasitization.

Delphastus pusillus is a predatory lady bird beetle that can feed on all stages of whiteflies. However, it prefers whitefly eggs and nymphs. Both immature and adult beetles are predacious. Delphastus is most likely to establish in hot spots and because it avoids feeding on parasitized whiteflies, it is compatible with them.

Beauveria bassiana is most effective against whitefly nymphs. Thorough coverage is necessary on leaf undersides where whitefly nymphs are found. Isaria fumosoroseus is another insect killing fungus that is commercially available.

Scouting for Greenhouse Whiteflies

- Yellow sticky cards can be used to monitor for adults.

- Look on underside of leaves for eggs, immature nymphs, pupae and adults on basil, costmary, lavender, lemon balm, lemon verbena, marjoram, mints, oregano, pineapple sage, rosemary, rue, sage, scented geraniums…

- Especially on overwintering stock plants.

Slugs

Slugs are mollusks and are covered by a coating of slime, which helps protect their bodies from desiccation. Slugs leave shiny patches of dried slime and tend to be found in cool, moist locations. Slugs are most active at night, and feed by chewing or rasping holes in leaves and stems. This damage can sometimes be confused with damage caused by caterpillars. Caterpillars usually leave pellet-like droppings.

Management requires improved sanitation (removal of debris under benches and weed control). Slugs hitchhike into the greenhouse on equipment or containers and flats that have been stored outdoors, or on unsterilized growing media (soil and sand). Carefully inspect incoming plants and containers for their presence. If possible, grow plants on expanded metal benches, not on wooden benches or on the ground. A copper barrier or strip may be wrapped around greenhouse bench legs or placed on raised beds as a barrier. The copper emits a small electrical charge that repels slugs. If areas are already infested, kill the slugs first, and then install the copper strips. In small areas, it may be possible to handpick and destroy the slugs. Handpicking is best done in the evening, about two hours after sunset.

Scouting for slugs

- Slugs feed at night on a wide range of crops.

- Look for holes in leaves and stems, and shiny mucous-like slime trails.

- Inspect areas under containers and damp areas in greenhouse

Disease Management

Accurate identification of diseases is essential for effective management. Some diseases of herbs include bacterial leaf spot, Botrytis blight, crown, and root rots, damping off, downy mildew, foliar nematodes, fungal leaf spots, powdery mildew, rusts, vascular wilts, and viruses. Non-infectious diseases or disorders caused by environmental concerns, nutritional imbalances, high soluble salts, improper planting depth (i.e. planting too deeply) or spray injury can mimic infectious diseases or predispose plants to infection. Infectious diseases usually begin on only a few plants, whereas disorders often affect a large number. Sanitation, the use of resistant cultivars, reduction of humidity levels and the appropriate use of fungicides and biological fungicides are all part of the integrated approach to disease management that is needed to produce high quality herbs.

Sanitation and the Use of Resistant cultivars

Start with a clean greenhouse and train employees in proper sanitation procedures. Discard old stock plants and unsold or “pet” plants that may harbor unwanted pests. Eliminate weeds both inside and outside the greenhouse. Sanitize the benches, walls, and floors to eliminate algae and pathogens. Algae provides a breeding ground for shore flies and fungus gnats. After the greenhouse has been sanitized, care must be taken to avoid recontamination with pests and pathogens. Dirty hose nozzles and tools and unsanitary growing conditions can result in re-infestation of potting media. Use hooks to keep hose nozzles off the floor.

Purchase seed and plant material from reliable sources. Use resistant varieties where feasible. Seed catalogues feature a limited number of disease resistant and tolerant varieties of herbs. For example, the basil cultivars ‘Aroma 2’ and 'Nufar' have resistance to Fusarium wilt. Produce stock plants from cuttings taken from vigorous, healthy plants that are free of insects and diseases and are true to type. Promptly remove any stock plants that are diseased or low in vigor. To avoid carrying insects and diseases into propagation areas, scout propagation houses before production areas.

Use separate greenhouses for herb production to help protect herbs from any insect or diseases that may be present on ornamentals and to make the treatment of herbs easier if pesticides are needed. Keep stock plants separate from production areas to help maintain clean stock plants.

Techniques to reduce humidity

High relative humidity encourages the development of many foliar diseases including Botrytis blight, downy mildew, powdery mildew, and Rhizoctonia web blight. Reduce condensation by using horizontal airflow (HAF). HAF fans help to keep air moving in the greenhouse. Air that is moving is continually mixed. The use of HAF helps to minimize temperature differentials in the greenhouse and prevent cold spots where condensation occurs. The mixed air along the surface does not cool below the dew point, so condensation does not form on plant surfaces. The use of computer control systems for environmental modification allows reduction of humidity levels to less than 85%.

Condensation can also be reduced by heating and venting the warm moist greenhouse air. Heat and vent 2 to 3 times per hour in the evening after the sun sets and early in the morning at sunrise. Many herb growers also use oversized vent fans and louvers to increase airflow in their greenhouses. Always water early in the day so the plant foliage can dry before nightfall to help prevent foliar diseases. Space plants so sufficient air circulation exists between them.

Biological Control of Plant Diseases

Biological control of plant diseases is the suppression of disease by the application of one or more biological control agents (BCAs) or biological fungicides. These beneficial BCAs include microorganisms such as specialized fungi, bacteria and actinobacteria (filamentous bacteria). Researchers have isolated specific strains of these organisms, many of which occur naturally in soils. Commercial products have been developed from these various strains and formulated with additives to enhance their performance and storage.

Since BCAs include living organisms, they are best used preventively before disease occurs and not as a rescue treatment for plants that are already diseased. BCAs should always be combined with proper sanitation and other cultural practices that promote plant health. Because biological fungicides are living organisms, they have a limited shelf life and need to be stored under proper conditions. Do not stockpile biological fungicides and be aware of the expiration date on their packages.

Growers can conduct their own trials on the effectiveness of biological fungicides by leaving a small portion of plants untreated to act as a control. This way their effect on crop growth and root health can be evaluated. Regular root inspections are needed to determine if roots are healthy and free from disease.

Specific Diseases

Bacterial Diseases

Herbs, like other greenhouse crops, are susceptible to bacterial diseases. Bacterial diseases generally survive in infected plants, in debris from infected plants and, in a few cases, in soil. Bacteria require a wound or natural opening in the plant to gain entry. Bacterial diseases of herbs include bacterial blight on scented geraniums, Pseudomonas leaf spot on basil and bacterial fasciation. Symptoms caused by bacteria are often indistinguishable from those caused by fungi and must be accurately identified by a diagnostic laboratory.

Scented geraniums are susceptible to bacterial blight caused by the pathogen Xanthomonas hortorum pv. pelargonii. Characteristic symptoms associated with this disease are wilting, small leaf spots and V-shaped angular lesions. However, infected plants may not show any symptoms. These infected plants appear healthy and can serve as a source of this disease for the more susceptible zonal and seed geraniums. Keep scented or specialty geraniums away from seed and zonal geraniums to reduce the potential for infection. Bacteria are easily spread by splashing water and by handling plants. Protect plants from water drip from hanging baskets and water condensation on the inside of the greenhouse.

Pseudomonas leafspots on basil are generally water-soaked and dark brown to black and angular in shape. Basil plugs may be especially vulnerable to infection due to the moist, wet conditions.

Bacterial fasciation or leafy gall results in abnormal branching and stem development near the base of infected plants of scented geraniums. Shoots are short, swollen, fleshy and produce misshapen leaves. Plants are not killed, but their growth is stunted. The bacterium (Rhodococcus fascians) is carried on infected cuttings. To manage, discard infected plants.

Management

- Disinfect all benches, equipment, and pots.

- Purchase culture-indexed plants known to be free of the most important bacterial pathogens.

- Do not use overhead irrigation. Always keep the foliage dry.

- Discard infected plants.

- At the end of the season, do not hold over any plants. Rake up any plant debris, as the bacteria can survive in dead leaves.

Scouting for Bacterial Leaf Spots

- Look for water-soaked brown or black spots on basil leaves.

- Spots are angular and surrounded by leaf veins.

Botrytis Blight

Botrytis cineraria may cause leaf blights, stem cankers, damping off and, occasionally, root rot. Plants may be attacked at any stage, but tender new growth and freshly injured and dying tissues are the most susceptible.

Symptoms: Botrytis produces gray, fuzzy-appearing spores on the surface of infected tissues under humid conditions. Almost all herbs are susceptible but basil, lavender, lemon balm, marjoram, parsley, and thyme may be especially vulnerable. Air currents and splashing water can easily disseminate the spores. Favorable environmental conditions include a film of moisture for 8 to 12 hours, relative humidity of 93% or greater, and temperatures between 55° and 65° F. After infection, colonization of plant tissues can occur at temperatures up to 70° F.

Management

Management of environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and duration of leaf wetness, used with sound cultural practices and the preventive use of fungicides or biological fungicides help prevent disease development.

- Control weeds and remove plant debris between crop cycles and during production. Dispose of diseased plants and debris in a plastic trash bag. To avoid spreading spores to uninfected plants keep the bag closed tightly while moving it through the greenhouse. Cover trash cans to prevent airborne spread of spores from diseased plant tissue.

- Provide adequate spacing of plants and the use of wire mesh benches to help improve air movement between plants.

- Proper planting dates, fertility, watering, and height management prevent overgrown plants, thereby reducing humidity within the canopy.

- Keep plants well fertilized but not excessively succulent. Avoid calcium deficiency.

- Always water in the morning, never late in the day. Rising daytime temperatures causes water to evaporate from the foliage and dry the leaf surface.

- Apply biological fungicides and fungicides preventively. They need to be used in conjunction with proper cultural and environmental controls.

Scouting for Botrytis Blight

- Look for leaf blight and gray fuzzy appearing spores on plant leaves during humid conditions.

- Tan stem cankers may develop on basil and rosemary.

Damping off, Crown and Root Rot

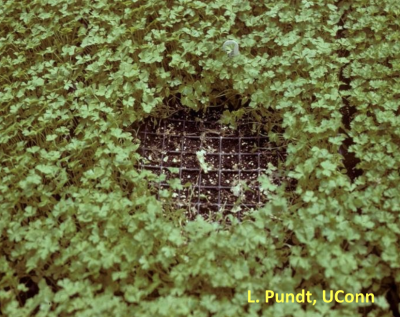

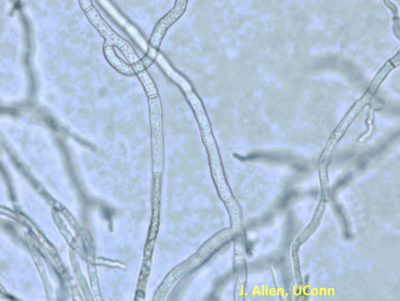

Damping-off is a common disease of germinating seeds and young seedlings. Several fungi such as Pythium, Rhizoctonia, Alternaria, Sclerotinia and Phytophthora cause damping-off. These fungi are easily transported from contaminated soil to pathogen-free growing media by infected tools, hose ends, water splash and hands. Young seedlings are most susceptible to damping-off. However, later in the crop cycle, the same pathogens may cause root and stem rots.

Symptoms

Infected seeds fail to germinate. Seedlings may also collapse with a dark, necrotic stem canker at the soil line. Seeds that germinate slowly, such as parsley, are especially susceptible.

When mature plants are infected with crown and root rot, leaves turn yellow and wilt and plants are stunted. Roots are often discolored and turn black or dark brown. When infected with root rots, the outer cortex of the root sloughs off leaving a central core. High moisture levels and high soluble salts favor the development of Pythium.

Drier soil, however, favors Rhizoctonia, an organism that is more active in the upper portion of the media. Rhizoctonia can also grow up from the soil causing web blight. Stems and leaves collapse rapidly; turn mushy with fine, web-like fungal mycelium present. Dense, lush plant canopies, and humid conditions favor the development of web blight. Proper plant spacing is needed to insure adequate airflow around plants. Rosemary, basil, mint, parsley, rue, thyme, and many other herbs are susceptible to web blight.

Manage fungus gnat larvae that may vector or spread soil borne pathogens such as Thielaviopsis, Pythium, and Phytophthora. Adult shore flies are capable of transmitting Pythium and other root rot pathogens. Many herbs, such as lavender, parsley, dill, mint (especially Corsican mint), basil, rue, sage, thyme, and rosemary are susceptible to fungi that cause crown and root rots.

Management

- Use commercially available soil-less mixes.

- Use properly produced composted-based growing mixes. Test electrical conductivity (EC) and pH levels before using to make sure the compost is properly finished.

- Disinfect all flats, pots, and tools between crop cycles.

- Do not re-use plug trays. It is very difficult to remove all the organic matter so that the commercial disinfectants can work.

- Use bottom heat to promote rapid germination of seed.

- Avoid over-watering, excessive fertilizer, overcrowding, planting too deeply and careless handling.

- Provide adequate light for rapid growth.

- Promptly rogue out infected plants. Discard entire flats.

- Manage fungus gnats and shore flies to reduce the potential for spread, especially during propagation.

- Use appropriate biological fungicides preventively at planting.

Scouting for damping off

- Common disease of germinating seeds and young seedlings.

- Seeds may fail to emerge (pre-emergence damping off).

- Young seedlings may wilt; water soaked stem lesion at soil line.

- Plants often die in a circular pattern.

Scouting for crown and root rots

- Leaves turn yellow and wilt.

- Plants may be stunted.

- Inspect roots. They may be discolored and turn brown or black.

- Laboratory analysis is needed to determine the causal agent.

Scouting for Rhizoctonia Web Blight

- Stems and leaves collapse with fine web-like fungal threads present.

- Dense canopies and humid conditions favor web blight.

- Many herbs including basil, mint, parsley, rosemary, rue, sage and thyme susceptible.

Downy Mildew of Basil

Downy mildew of basil was first reported in the US in 2007 in Florida. In 2008, it was widespread in the Northeast. Basil downy mildew is caused by the host specific fungus like organism, Peronospora belbahrii. Favorable environmental conditions include as least four hours of leaf wetness, high humidity at night and moderate temperatures (~68 °F).

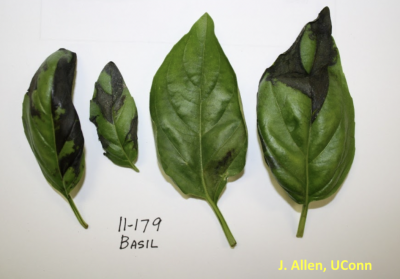

Symptoms

Mild yellowing and leaf cupping occur on young seedlings. During conditions of high relative humidity, dark purplish-brown to gray fungus-like sporulation develop on the underside of the lowermost leaves. Yellowing or mottling of the leaves resembles a nutrient (magnesium) deficiency.

Management

- Start with disease free seed. Ask if your supplier is stream treating their susceptible basil varieties.

- Purchase basil downy mildew resistant varieties. Disease resistance is rarely immunity, so some symptoms may occur. Rutgers Obsession DMR is available for both field and potted pot production. Rutgers Devotion DMR is available for potted plant production. Both varieties are released from the Rutgers breeding program and sold by VDF Specialty Seeds. Prospera is an organic basil seed from Johnny’s Selected Seeds. Proven Winners has developed the downy mildew resistant variety, Amazel, which is sold as cuttings, for the seed is sterile. None of these varieties are fully resistant but will develop the disease more slowly than the fully susceptible varieties.

- Use a combination of heating and venting, especially at night to reduce greenhouse humidity.

- Reduce periods of leaf wetness by proper plant spacing, the use of open wire benches and watering early in the day when plants will dry out quickly.

- Promptly destroy any infected plants and carefully remove them from the greenhouse by placing in tightly closed plastic bags.

- Use appropriate fungicides preventively.

Scouting for Basil Downy Mildew

- Yellowing between the veins resembles a nutritional disorder.

- Look for purplish brown to grayish sporulation on the underside of leaves on susceptible basil varieties.

Foliar Nematodes

Foliar nematodes (Aphelenchoides spp.) are microscopic roundworms that live in plant foliage and can occasionally occur on herbs. These nematodes enter plant tissue through stomates and then feed and reproduce within the plant. Foliar nematodes can be spread by splashing water. Affected leaves may turn pale green, yellow or brown. Symptoms are easily confused with those caused by fungal or bacterial leaf spots, so samples need to be submitted to a diagnostic laboratory for confirmation.

Fungal Leaf Spots

Fungal leaf spots caused by Alternaria, Septoria and other fungi may occasionally be seen on herbs. Alternaria leaf spots are generally dark brown to black with a yellow border. Septoria leaf spots are small and grayish brown with a dark brown edge. With a hand lens, you may see the small dark fruiting bodies of septoria (which look like pepper) in the center of the leaf spot on lavender. Splashing water spreads fungal spores. These diseases may be carried over from season to season on infected seed or plant debris in the field.

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum causes reddening of the foliage and dieback on St. John's-wort (Hypericum). It can spread by contaminated seeds and then by water splash via overhead irrigation. Hypericum perforatum 'Helos' has shown tolerance to the disease. Some seed companies test their seed for this disease.

Management

Growers should select the healthiest and most disease resistant cultivars that are available. Cultural practices used to manage Botrytis will also help to manage leaf spots.

Fusarium wilt of Basil

Vascular wilts are diseases in which the vascular tissue is systemically invaded by pathogens. As the vascular system is clogged, plants wilt. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. basilicum causes fusarium wilt of basil. This disease was first reported in the United States on infected basil seed in the early 1990s.

Symptoms

A downward bending, or cupping of the leaves is often the first symptom of fusarium wilt. Sometimes the top of the stem bends like a shepherd's crook. On large-leafed cultivars, defoliation may occur. In later stages of fusarium wilt, brown streaks can be seen on the stem. Basil can also wilt due to water stress, root rot diseases, or Botrytis stem canker, so confirmation is recommended by sending samples to a diagnostic laboratory. Above ground symptoms of fusarium wilt may be similar to those caused by root rot pathogens. However, plants infected with fusarium wilt generally have healthy roots compared to plants wilted due to a root rot disease.

Management

Fusarium wilt is very difficult to manage. Begin with disease-free seed and request that your seed suppliers test their seed. However, testing is not a 100% guaranteed because conventional testing methods are not very sensitive. The varieties ‘Aroma 2’ and ‘Nufar’ have resistance to fusarium wilt. While these varieties are resistant to Fusarium wilt, they are susceptible to basil downy mildew. Remove infected plants to reduce disease spread to nearby plants. Clean and disinfest greenhouses after Fusarium occurs. Fusarium is a soil inhabitant that can become established in the field. Crop rotation should exclude members of the mint family, for some mints can be symptomless carriers of Fusarium.

Powdery Mildew

Most growers are familiar with the white, powdery growth that is characteristic of powdery mildew. Powdery mildew, unlike many foliar diseases, does not need free moisture on the leaf for spores to germinate. Favorable environmental conditions include high relative humidity (greater than 70%) and temperatures between 68° to 86° F. Fungal spores are easily spread by air currents and splashing water. Once a spore lands on a plant, it may take as little as 3 days, but more often 5 to 7 days, for the infection to develop into a visible colony.

Symptoms

Powdery mildew develops first on older leaves and is often overlooked. Scout weekly for early detection. Inspect susceptible crops and scout areas near vents, or any location with a sharp change between day and night temperatures. Look on both the upper and lower surfaces of leaves for signs of the white, powdery fungal growth. Use a hand lens to see the white fungal threads radiating from a central point and the chains of powdery mildew spores. These structures distinguish this disease from the whitish-spray residue, which has a droplet-like outline. Many herbs such as rosemary, sage, mint, St. John’s wort are susceptible to powdery mildew.

Management

- Remove infected plants. Place affected plants in a plastic bag to avoid spreading the airborne spores to uninfected plants as you remove infected material.

- Use proper spacing to increase air movement around plants.

- Keep relative humidity levels below 70 % in the greenhouse.

- Use wire mesh or other benching that facilitates air movement.

- Clean the greenhouse between crops. Powdery mildew may overwinter on certain weed hosts.

- Use resistant cultivars whenever possible.

- As soon as powdery mildew is detected, use appropriate biofungicides or fungicides or eradicants such as mineral oils.

Scouting for Powdery Mildew

- Look for faint, white fungal threads on mint, rosemary, sage...

- Look on older leaves, and both upper and lower leaf surfaces.

- Look for the fungal threads and chains of spores with a hand lens to distinguish from powdery-white spray residue.

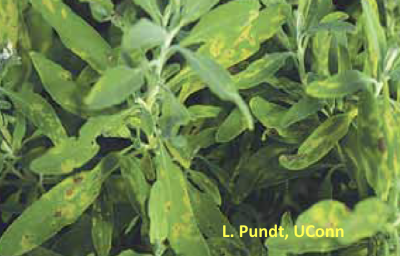

Rusts

Rust fungi are highly specialized fungi with complex life cycles. Some types of rust may need two different hosts to complete their life cycle, whereas other types only need one host. Cool temperatures and free moisture on leaves favor their development.

Symptoms

Rust diseases are easy to identify by the reddish-brown spores found in masses on the undersides of leaves. Herbs such as mint, lemon grass, tarragon, and St. John’s wort may become infected with rust diseases. Rust caused by Puccinia menthae may infect spearmint and peppermint. This type of rust does not need an alternative host to complete its development. Look for yellow leaf spots on the upper surface and cinnamon-brown rust pustules on the undersides of the lower leaves. A rust disease caused by Puccinia nakanishikii may occur on lemon grass. Elongated, stripe-like rusty brown lesions occur on the undersides of leaves.

Management

- Destroy infested plants promptly.

- Do not take cuttings from infested plants. Discard plants and try a more resistant variety. The improved spearmint or Kentucky Colonel mint is less susceptible than the standard spearmint. The peppermint cultivars 'Murray Mitcham' and 'Todd's Mitcham ' are resistant to rust under moderate disease pressure.

- As soon as rust is detected, use appropriate fungicides.

Scouting for Rusts

- Rusts are easy to identify by their reddish-brown spores found in masses.

- Some herbs susceptible to rusts include lemon grass, spearmint, peppermint, and French tarragon.

Viruses

Viruses are ultra-microscopic infectious particles that multiply only within living host plant cells. Viruses can spread systemically throughout the host plant and some plants may be infected even when symptoms are not apparent. Some, like tobacco ringspot virus on rosemary, have a narrow host range, while others, like cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and tospoviruses (such as impatiens necrotic spot virus and tomato spotted wilt virus) can infect a wide variety of herbs as well as other plants. There is no cure for infected plants. Virus infections are usually systemic and are often transmitted through vegetative propagation. Plants vegetatively propagated from stock plants infected with a virus also carry the virus. Depending upon the virus type, transmission can occur in several ways. Tobacco mosaic virus can be transmitted through the handling of plants or the use of contaminated tools, but not by insects. However, insect vectors can transmit several viruses. For example, aphids transmit cucumber mosaic virus and thrips vector tospoviruses.

Symptoms

Symptoms include mosaic patterns on the foliage, leaf crinkle or distortion, chlorotic streaking, ringspots, line patterns and distinct yellowing of veins. Plants may also be stunted. However, plants can be infected and not show any visible symptoms.

Management

Submit potentially infected plants to a plant diagnostic laboratory for accurate identification. Management includes starting plants with virus-free seed or cuttings, eradication of weed hosts, controlling insect vectors, and discarding infected plant material.

Scouting for Viruses

- Symptoms include mosaic patterns, leaf crinkle or distortion, chlorotic streaking, ringspots, unusual line patterns and stunting.

- Some viruses have a wide host range, some have a narrow host range.

- There is no cure.

Non-infectious diseases or disorders

Non-infectious diseases or disorders caused by environmental concerns, nutritional imbalances, high soluble salts, improper planting depth (i.e. planting too deeply) or spray injury can mimic infectious diseases or predispose plants to infection. Infectious diseases usually begin on only a few plants, whereas disorders often affect a large number.

References

Anon. 2000. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 40. Parts 150-189. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. See Part 180 Tolerances and Exemptions from Tolerances for Pesticide Chemicals in Food. See Section 180.41 Crop Group Tables.

Bartok, J. 2016. Insect Screening can be an Important Pest Management Tool. https://ipm-cahnr.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3216/2023/01/2016insectscreeningjb.pdf

Casey, C. (Ed.) 2000. Integrated Pest Management for Bedding Plants. A Scouting and Pest Management Guide. New York State IPM Program. IPM Bulletin No. 407. 117 pp.

Chase, A. 2006. Herb Diseases Take Knowledge to Combat Successfully. GMPro. 2 pp.

Cox, D., and L. Craker. 1993. Growing Herbs as Bedding Plants. University of Massachusetts Floral Notes. 6(3): 2- 6.

Currey, C.J. and T. Z. Mazur. 2018. Spinning the Herb Wheel. Grower Talks. August 2018. 82(40): 66-69.

Currey, C.J. 2018. Fertilizing Containerized Herbs. GrowerTalks. December 2018. 82(8):76-78.

Currey, C.J. 2019. Managing Temperature in Herbs. GrowerTalks. February 2019. 82 (10):62-65.

Farr, D.F.; Bills, G.F. Chamuris, G.P, and A.Y. Rossman. 1989. Fungi on Plants and Plant Products in the United States. APS Press. The American Phytopathological Society. St. Paul, Minnesota. 1252 pp.

Frank, S., E.A. Shearin and J. Baker. 2019. Insect Screening for Greenhouses. NC State Extension Factsheet. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/insect-screening-for-greenhouses

Gibson, J.L., B. Whipker, and R. Cloyd. 2000. Success with Container Production of Twelve Herb Species. North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension. Horticulture Information Leaflet 509.

Greer, L. 2000. Organic Greenhouse Herb Production. Horticulture Production Guide. Appropriate Technology Transfer for Rural Areas (ATTRA). http://www.attra.org

Hausbeck, M.K., R. A. Welliver and M.A. Derr. 1992. Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus Survey Among Greenhouse Ornamentals in Pennsylvania. Plant Disease. 76:795-800.

Horst, K. R. 2013. Westcott's Plant Disease Handbook. 8th edition. Spring Science and Business Media. 848 pp.

Howard, R., J., J.A. Garland, and W.L. Seaman (Ed). 1994. Herbs and Spices In Diseases and Pests of Vegetable Crops in Canada. The Canadian Phytopathological Society and Entomological Society of Canada. Ottawa, Canada.

Mattson, N., and M. Daughtrey. 2016. Basil Fusarium Wilt. E-Gro Edible Alert. 1(2) 4 pp. http://www.e-gro.org/pdf/E102.pdf

McGrath, M.T. 2020. Basil Downy Mildew. https://www.vegetables.cornell.edu/pest-management/disease-factsheets/basil-downy-mildew/

McGrath. M. T. 2019. Managing Basil Downy Mildew in the Greenhouse. e-Gro Edible Alert. 4(7) March 2019. http://www.e-gro.org/pdf/E407.pdf

Pundt, L. and C. Smith. 2020. Preventive Use of Biological Fungicides in the Greenhouse for Transplant Production. CropTalk. 16(3): 4-5.

Raudales, R. and L. Pundt. (Ed.) 2021. New England Greenhouse Floricultural Recommendations: A Management Guide for Insects, Diseases, Weeds and Growth Regulators. 2021-2022. New England Floriculture, Inc. Winooski, VT. 246 pp.

Smith, T. 1999. Pest Management for Herbs. UMass Extension Floral Notes. 11(4):4-5.

Smith, T., and L. Pundt. 2001. Pest Management for Vegetable Bedding Plants. New England Greenhouse Conference Fact Sheet 1. 8 pp.

Shore, S. 1999. Growing and selling Fresh-Cut Herbs. Storey Books, Pownal, VT. 453 pp.

Thomas, P. 1997. The Challenges and Rewards of Herb Production. Greenhouse Product News. July issue. 60-65.

Traven, L. 1999. Herbs. In Tips on Growing Bedding Plants. 4th edition. 1999. Ohio Florist Association. Columbus, Ohio. 159 pp.

Wyenandt, C, A., J. E. Simon, R. M. Pyne, K. Homa, M. T. McGrath, S. Zhang, R. N. Raid, L. J. Ma, R. Wick, L. Guo, and A. Madeiras. 2015. Basil Downy Mildew (Peronospora belbahrii): Discoveries and Challenges Relative to Its Control. Phytopathology. 105:885-894.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this publication was provided by a grant from the New England Greenhouse Conference.

Revised by L. Pundt, 2021

For a listing or selected insecticides and miticides for use on herb bedding plants, see:

For a listing of selected fungicides labeled for herb bedding plants see:

For a listing of scouting guidelines and biological control options see:

TABLE 1: SOME KEY PESTS OF HERBS

| Plant | Pest (s) |

| Basil | Primarily thrips, also aphids, whiteflies

Bacterial Leaf Spot, Botrytis blight and Stem Canker, Downy Mildew, Fusarium wilt, Pythium and Rhizoctonia root rots, Rhizoctonia web blight, Impatiens necrotic spot virus and tomato spotted wilt virus |

| Lavender | Aphids, leafhoppers, whiteflies, spider mites, mealybugs

Primarily Phytophthora crown and root rots, also Botrytis blight, Septoria leaf spot |

| Lemon Balm | Primarily spider mites, aphids, whiteflies

Botrytis blight |

| Lemon Grass | Spider Mites, thrips, rust |

| Lemon Verbena | Aphids, spider mites and whiteflies |

| Marjoram | Whiteflies, Botrytis blight |

| Mint | Primarily whiteflies, spider mites, leafhoppers, aphids, thrips, four-lined plant bugs

Crown and root Rots, Rhizoctonia web blight, powdery mildew, rust (peppermint and spearmint), tomato spotted wilt virus |

| Parsley | Aphids, Thrips, Primarily root rots, also Botrytis blight, Rhizoctonia web blight |

| Rosemary | Whiteflies, aphids, leafhoppers, thrips, and mealybugs

Primarily powdery mildew, also Phytophthora, Pythium and Rhizoctonia root rots, Rhizoctonia web blight |

| Rue | Aphids, whiteflies

Crown and root rots |

| Sage | Primarily whiteflies, also spider mites, leafhoppers, aphids, and thrips

Primarily powdery mildew |

| Scented Geranium | Primarily whiteflies

Bacterial blight (Xanthomonas), Bacterial fasciation |

| St. John’s wort | Anthracnose, powdery mildew |

| Thyme | Aphids, thrips

Crown and Root Rots, Rhizoctonia web blight, Botrytis blight |

Copyright 2023 by the University of Connecticut. All rights reserved.