Bacterial diseases are common in tomatoes and also very frustrating to tomato growers since they may cause significant economic losses and are difficult to control. Once established in a field, bacterial diseases are nearly impossible to control if weather conditions favor disease development. Therefore, early prevention is the key to avoiding serious losses.

Bacterial spot, bacterial speck and bacterial canker are the most important diseases of tomato in the northern United States. All three can cause localized epidemics during warm (spot and canker) or cool (speck), moist conditions. Bacterial spot and speck can cause moderate to severe defoliation, blossom blight, and lesions on developing fruit. Bacterial canker causes wilt, vascular discoloration, scorching of leaf margins and lesions on fruit.

Disease Symptoms

Bacterial canker. Primary or systemic symptoms of bacterial canker (from infections originating in seeds or young seedlings) include stunting, wilting, vascular discoloration, development of open stem cankers and fruit lesions. When affected stems are split open lengthwise, a thin, reddish-brown discoloration of the vascular tissue is observed, especially at the base of the plant. On young seedlings in the greenhouse, lesions may appear as raised pustules on leaves and stems. These plants rarely survive the season in the field. Secondary symptoms in the field include leaf “firing” (necrotic marginal leaf tissue adjacent to a thin band of chlorotic tissue) and fruit lesions. Spots on fruit are relatively small (1/32 to 1/16 in), usually surrounded by a white halo (“bird’s-eye” spots). Canker bacteria may also invade internal fruit tissues, causing a yellow to brown breakdown.

Bacterial spot and speck. Foliar symptoms of bacterial spot and speck are very similar. Small, water soaked, greasy spots about an 1/8 inch in diameter appear on infected leaflets. After a few days, these lesions are often surrounded by yellow halos and the centers dry out and frequently tear. Lesions may coalesce to form large, irregular dead spots. In mature plants, leaflet infection is most concentrated on fully-expanded and older leaves and some defoliation may occur. Spots may also appear on seedling stems and fruit pedicels. In some cases, blossom blight may occur, causing flower abortion. Bacterial spot and speck can usually be differentiated by symptoms on immature fruits.

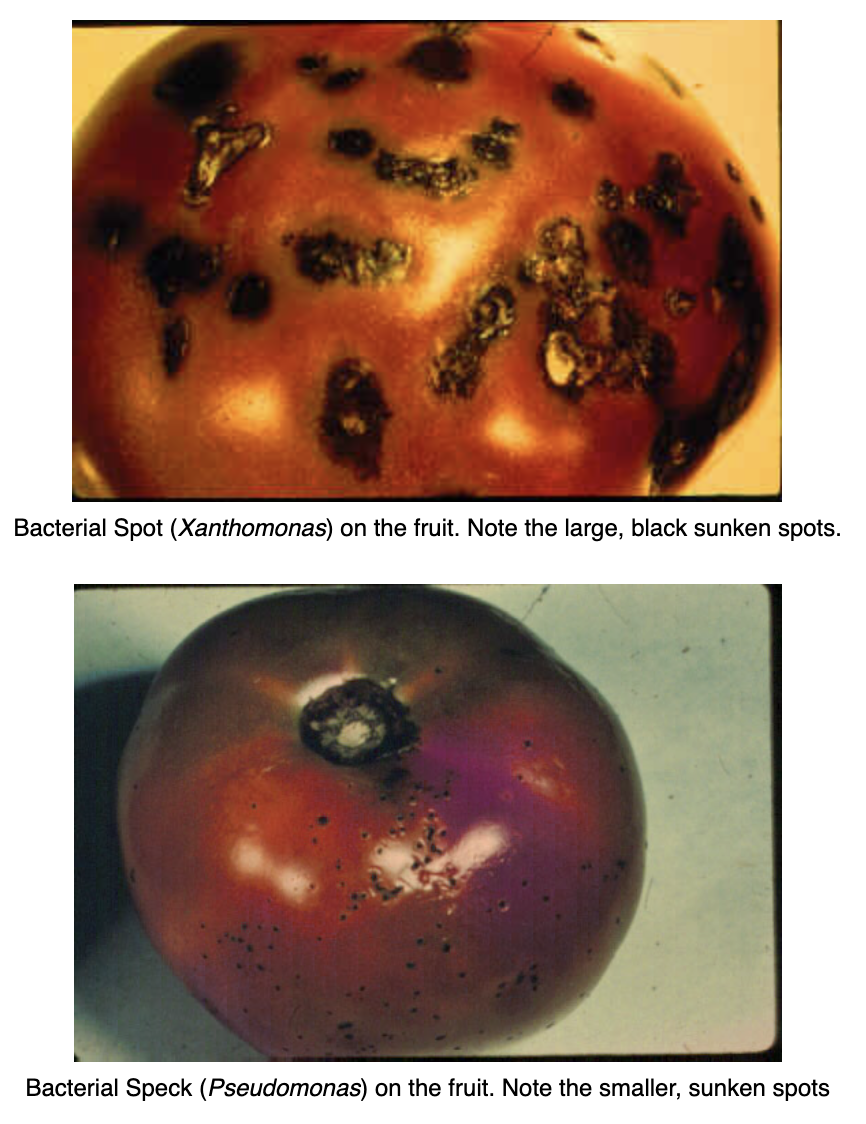

Bacterial spot lesions on fruit are small water-soaked spots that become slightly raised and enlarged until they are about ¼- 1/3 inch in diameter. The centers of these spots later become irregular, light brown, slightly sunken with a rough, scabby surface. In the early stages of infection, a white halo may surround each lesion at which time it resembles the fruit spot of bacterial canker. Small lesions that have not yet become scabby are often confused with lesions of bacterial speck.

Bacterial speck appears on immature fruit as a black, slightly sunken stippling, eventually causing lesions less than 1/16 inch in diameter. Fruit lesions are not initiated on mature fruit in either disease.

Disease Management

Bacterial spot is caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, which can be carried as a contaminant on the surface of infested seed and has been found to overwinter in soil associated with plant debris. Bacterial speck is caused by another bacterium, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. This bacterium may also be seedborne and can overwinter on plant debris in soil and on the roots of many perennial plants. Bacterial canker is caused by Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis, which, unlike the spot and speck pathogens, has the ability to infect tomato plants systemically. It is seedborne and can survive on infested plant debris in soil.

All three organisms may exist at low populations on leaf surfaces of symptomless plants. At the onset of favorable conditions, these low populations can increase rapidly and bacteria can then enter plants through stomata or small wounds and begin infection. Bacteria can spread rapidly with spattering rain and widespread epidemics may develop. Penetration of tomato fruit occurs through wounds created by windblown sand and soil particles, breaking of hairs or by insect punctures. Optimal conditions for bacterial spot and canker are high moisture, high relative humidity, and warm temperatures (75 – 90oF). Bacterial speck is more likely to occur under cool (64 – 75oF), moist conditions.

Interventions to reduce the risk of losses from bacterial diseases can be made during the following four phases of tomato production. The earlier the intervention (i.e., at the seed preparation stage), the greater the likelihood of reducing disease incidence and severity:

- Site selection

- Seed purchase and preparation

- Transplant/seedling production

- Field plant production

Site selection. Rotate tomatoes with non-solanaceous crops (solanaceous crops include tomato, pepper and eggplant) with at least 2-3 years between tomato crops. Since the bacterial canker pathogen has been reported to persist for up to five years in the field, an even longer rotation is advisable if canker has been a problem. Peppers are highly susceptible to bacterial spot, and should never be used in rotation with tomatoes.

Seed purchase and preparation. Plant only seed from disease-free plants or seed treated to reduce any bacterial populations. Seed should be purchased from a reputable producer with a good track record for providing quality seed. Seeds should have been tested and/or treated for bacterial pathogens. Treatments include

- fermentation of tomato pulp and seeds at room temperature for 4-5 days,

- soaking seeds in 0.6 – 0.8% acetic acid for 24 hrs. at 70oF,

- soaking seeds 5-10 hrs. in 5% hydrochloric acid,

- hot water treatment of seeds (122oF for 25 minutes), or

- sodium hypochlorite (bleach) treatment [20-40 mm soak of seeds in 1% sodium hypochlorite (20% bleach)]. Some decrease in germination may occur as a result of these treatments.

Transplant/seedling production. In the northern United States, tomato seedlings are usually produced in greenhouses starting in late winter and transplanted to the field in May or June. We do not recommend use of “bare root” transplants from the southern U.S. Keeping the seedlings free of disease during the seedling phase is critical for production of a healthy crop. Bacterial diseases can make their first appearance on seedlings in the greenhouse, although they rarely cause massive damage at this point. However, bacterial diseases initiated in seedlings will lead to very poor plant performance in the field if environmental conditions favor disease development.

Symptoms of bacterial spot and speck in the greenhouse are similar: small necrotic spots may be found on the leaves, petioles, or stems. Spots of bacterial canker appear more raised and whitish in color. Sometimes seedlings that are under conditions of nutrient stress, especially if they have been held too long before transplanting, may develop dark purple spots that appear superficially similar to bacterial spot or speck. Plants usually outgrow these symptoms once they have been transplanted. If spots are observed on tomato seedlings in the greenhouse, samples should be submitted to a diagnostic clinic or extension specialist for confirmation. Usually seedlings with bacterial disease symptoms, and those nearby, are destroyed. Sometimes all plants in the greenhouse are destroyed. Therefore, it is best to avoid bacterial diseases by planting ‘clean’ seed, using new or sanitized plant flats or trays, avoiding over-watering, allowing the foliage to dry before nightfall, and avoiding handling the plants when they are wet.

Exotic or experimental pepper or tomato varieties, or varieties from seed saved by the grower, should not be planted in the same house as the bulk of the transplants unless the seed have been treated as described above. After each crop, clean greenhouse walls, benches etc. with hot soapy water, followed by thorough rinsing and treatment with a disinfectant. If possible, close up the greenhouse after transplant production is completed to allow natural heating during the summer. Use only new plug trays and pathogen-free planting mixes.

Field plant production. In the field, control irrigation to minimize the time foliage is wet, and avoid working among wet plants to minimize spread of disease. Plants should not be pruned when they are wet, and pruning tools must be sanitized. Applications of mancozeb plus copper soon after transplanting and throughout the season may help retard development and spread of bacterial spot and speck. This practice is not effective for management of bacterial canker. Applications of Actigard ®(Novartis Crop Protection), a plant protection compound in a new class of chemicals called “plant activators,” has been shown to significantly reduce bacterial spot and speck in field trials. Actigard® is not effective against bacterial canker.

By: Sally A. Miller, Associate Professor, Ohio State University – OARDC, Department of Plant Pathology, 1680 Madison Avenue, Wooster, OH 44691.

Published: Proceedings. 1999. New England Vegetable and Berry Growers Conference and Trade Show, Sturbridge, MA. p. 323-325.

Updated by: T. Jude Boucher, IPM, University of Connecticut. 2012

Information on our site was developed for conditions in the Northeast. Use in other geographical areas may be inappropriate.

The information in this document is for educational purposes only. The recommendations contained are based on the best available knowledge at the time of publication. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. The Cooperative Extension System does not guarantee or warrant the standard of any product referenced or imply approval of the product to the exclusion of others which also may be available. The University of Connecticut, Cooperative Extension System, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.