What to be on the lookout for…

Squash Vine Borer

Two farms in CT recently reported finding Squash Vine Borer (SVB) moths in traps, one of which was in Berlin and caught 13 SVB moths. This indicates female adult moths will lay their eggs at the base of thick-stemmed cucurbit crops (e.g. summer squash, zucchini, giant pumpkins, and some winter squash) within the next couple of weeks. Fortunately, thin-stemmed crops like cucumber, watermelon and butternut squash are less habitable for the larvae and therefore less likely to be impacted.

Infestations of SVB can be minimized by using floating row cover, trapping moths, and late plantings to avoid peak SVB egg-laying activity. Insecticides can also help with reducing populations.

You can monitor SVB with Scentry Heliothis pheromone traps. The threshold for spraying is 5 moths/trap for vining cucurbits. Once larvae have bored inside the stem, insecticide application will have little control, so begin protecting your crops promptly. Thoroughly treat the base of stems to target hatching larvae. Some selective materials used for caterpillars in squash, such as spinosyns and Bacillus thuringiensis aizawi, have demonstrated efficacy in trials.

See the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more information on insect control options for SVB.

Potato Leafhoppers & Hopperburn

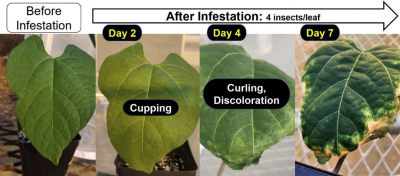

Potato leafhoppers (PLH) primarily impact potatoes, beans, and eggplant, but they are not picky eaters and have a wide host range, including other legumes (clover, soybean, alfalfa), solanaceous (tomato, pepper), and other vegetables (lettuce, celery). The presence of nymphs indicates an established population. Signs of injury begin with leaf veins turning pale, followed by the yellowing or browning of areas of the leaf or leaf tips which is known as "hopperburn". Leaves become brown, curl up, and die. Plants may be stunted and yields reduced or lost. PLH can also be a vector of many viruses.

Scout using sweep nets or by shaking plants to see if adults fly up when the plant is disturbed. Nymphs can be counted on the underside of leaves. Seedling beans should be treated if they have 2 adults per foot of row. From 3rd trifoliate leaf to bud stage, treat when PLH exceed 1 nymph per leaflet or 5 adults per foot of row. Repeat application in 7 to 10 days if necessary. In potatoes, treat if more than 1 adult per sweep is found, or more than 15 nymphs are found per 50 leaves. Be sure to treat lower leaf surfaces when spraying. In fields where systemic seed treatment was used, foliar treatment should not be needed before bloom.

See the New England Vegetable Management Guide for recommendations on insect control options for beans, potatoes, or eggplant. Additional information on management strategies can be found on the page for “Insects That Can Be Controlled By Row Covers”.

Ozone Injury

Ozone is the most common air pollutant in the eastern United States. Ozone is formed when the combustion of fossil fuels react with oxygen in the presence of sunlight. It moves from areas of high concentration (cities, heavy traffic areas) to nearby fields simply by wind. Common symptoms of ozone injury are very small, irregularly shaped spots that are dark brown to black or light tan to white on the upper leaf surface. Injury is usually more pronounced at the leaf tip and along the margins. It is most likely to occur when the weather is hot, humid, and air masses are stagnant.

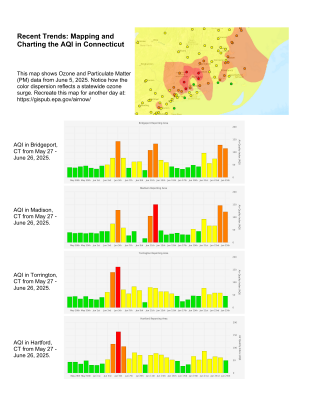

There have been a few ozone level surges this month reaching toxic levels for crops in Connecticut, with severity changing slightly depending on the precise location in the state. Ozone injury in susceptible vegetable varieties develops when ozone levels are over 80 ppb for four or five consecutive hours, or 70 ppb for a day or two when vegetable foliage is at a susceptible stage of growth. Typically, the most susceptible vegetable crops include cucumber, potatoes, watermelon, cantaloupe, snap beans, pumpkins, and squash.

The best recommendation for managing susceptible crops in when ozone levels are high is to whatever extent possible, avoid additional stresses on plants. Do not apply unwarranted pesticides or nutrients during this period. Note which varieties show fewer symptoms and plan to select varieties that are less susceptible in the future.

For more information on the relationship between the Air Quality Index (AQI) and Ozone levels, visit the Air Quality Guide for Ozone and Particle Pollution. For example, ozone concentrations would be 71-85 ppb when AQI is 101-150. To monitor local trends, vist airnow.gov.

https://www.airnow.gov/aqi/aqi-basics/

Sweet Corn Pests - Trap Count Update

European Corn Borer (ECB)

With the significant change in weather this past week, corn has really started to take off, and so have the respective pests. This week a farm in Shelton, CT reported data from their heliothis traps which included 2 ECB NY moths, 0 IA, and 1 Hybrid for a total of 3 ECB. A farm in Berlin also reported finding 1 ECB NY moth and 1 ECB Hybrid moth in their traps, so ECB populations are on the rise. Corn with newly emerging tassels should be scouted weekly for the presence of ECB larvae. Inspect the tassels of 50 to 100 plants, in groups of 5 to 20 plants throughout the field. Treat if more than 15% of the plants have one or more larvae present. Use of selective products to control ECB will conserve natural enemies of aphids and ECB.

Corn earworm (CEW)

Traps have just been set up to start tracking CEW populations, and early checks indicate empty traps. CEW is important to continue scouting for as they feed on a wide range of crops, and among vegetables, they favor corn and tomato (hence it is also known as “tomato fruitworm”.

Fall armyworm (FAW)

Since FAW do not overwinter in New England, infestations result from moths carried northward on storm fronts usually around mid-July and into September. But in recent years, they have been spotted as early as mid-June. FAW flights are sporadic and unpredictable and do not necessarily correspond with CEW flights, so monitoring with phermone traps when corn is in whorl stage is very useful.

See the New England Vegetable Management Guide for detailed management strategies for all sweet corn insect pests.

Photo: David Handley

Continue to be on the lookout for...

Striped and Spotted Cucumber Beetles

Brassica and Solanaceous Flea Beetles

Small Farm Innovations

Project Forms

Due: July 15th

Students in the UConn College of Engineering and College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources want to help farmers make their infrastructure and environmental impact ideas become a reality.

Must be a production farmer located in Connecticut with at least 1 year of production experience operating their own farm business.

Submit your application for the Small Farm Innovations Project today!

Want the New England Vegetable Management Guide and/or Northeast Vegetable and Strawberry Pest ID Guide at your fingertips?

Stay in touch with us

- Share what you see: We're here to assist with identification, management strategies, and guidance on best practices. Send us a photo/message via text at 959-929-1031.

- Facebook Group: UConn Extension moderates a private Facebook group specifically for commercial vegetable producers. It is a space to share photos of insects and diseases you find in your fields, ask questions, share ideas, and stay engaged with growers across the state. Join the "UConn Extension - Vegetable IPM" Facebook Group

- Schedule a consultation: Would you benefit from meeting with an Extension Specialist at your farm to provide insight on pest or disease identification, management strategies, and more? If so, please contact our Vegetable Extension Specialist, Shuresh Ghimire, to setup a farm visit. Contact him at shuresh.ghimire@uconn.edu or 860-870-6933.

Contact Information

Shuresh Ghimire, Vegetable Extension Specialist: shuresh.ghimire@uconn.edu

Nicole Davidow, Vegetable Extension Outreach Assistant: nicole.davidow@uconn.edu

Vegetable IPM Office Phone Number:

860-870-6933

Vegetable IPM Cell Phone Number:

959-929-1031 (feel free to text/iMessage photos)

Vegetable IPM Pest Alert Audio Recording:

860-870-6954

Thank you for reading!

This report was prepared by Nicole Davidow, Outreach Assistant, and Shuresh Ghimire, Commercial Vegetable Specialist, UConn Extension.

The information in this document is for educational purposes only. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this report if it is in conflict with the label. UConn Extension does not guarantee or warrant the standard of any product referenced or imply approval of the product to the exclusion of others which also may be available. The University of Connecticut, UConn Extension, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources is an equal opportunity program provider.